Welcome to As Built! This week is about hardware engineering, and specifically the various product—and program—market fits that must be cultivated over multi-year development cycles. Next week, back to nuclear, to pick up with nuclear fuel part 2 and the pathways to enhance nuclear fuel security. For those in the U.S., Happy Thanksgiving!

Complex hardware systems occupy a unique category of technology development. Think satellites, reactors, autonomous boats, and launch vehicles. Unlike software that ships in sprints or simpler hardware that iterates in months, these systems have multi-year development horizons.

Such extended timelines come with a fundamental problem: the world refuses to stand still while you build.

The market assumptions that justify starting a complex hardware program rarely survive to its completion. Customer needs evolve, emerging technologies present better offerings, and new entrants leverage resources that didn’t exist when you began.

Meanwhile, regulations shift, investor appetite can swing from euphoria to terror (and sometimes back), and public opinion can turn big accomplishments into political liabilities. What looked like a goood fit in year one can be eroded by year five.

The challenge extends beyond just timing.

Hardware programs must maintain alignment across multiple stakeholder groups: customers, regulators, investors, government administrations, the public, and others. This goes beyond product-market fit, to a complete program-market fit. Lose support from any critical stakeholder, particularly around funding milestones, and the program stumbles, regardless of technical merit.

While the market can shift quickly, hardware programs tend to accumulate substantial inertia. Changing course is a process. Teams lock into architectures, supply chains crystallize, and regulatory pathways narrow.

Success requires anticipating not where the market is, but where it will be throughout the course of development. While perfect foresight is impossible, the best programs come close—as the hockey adage goes, skating to where the puck will be.

Multiple Cycles Matter

Consider a six-year development program. Along the way, there might be three key financing milestones. At each, you must demonstrate market alignment and a path to profitability. At year six, the hardware is operational and it’s time to start scaling up actual profits.

Yet, the challenge is that each stakeholder group operates on its own cycle, and they all rarely synchronize.

Customers

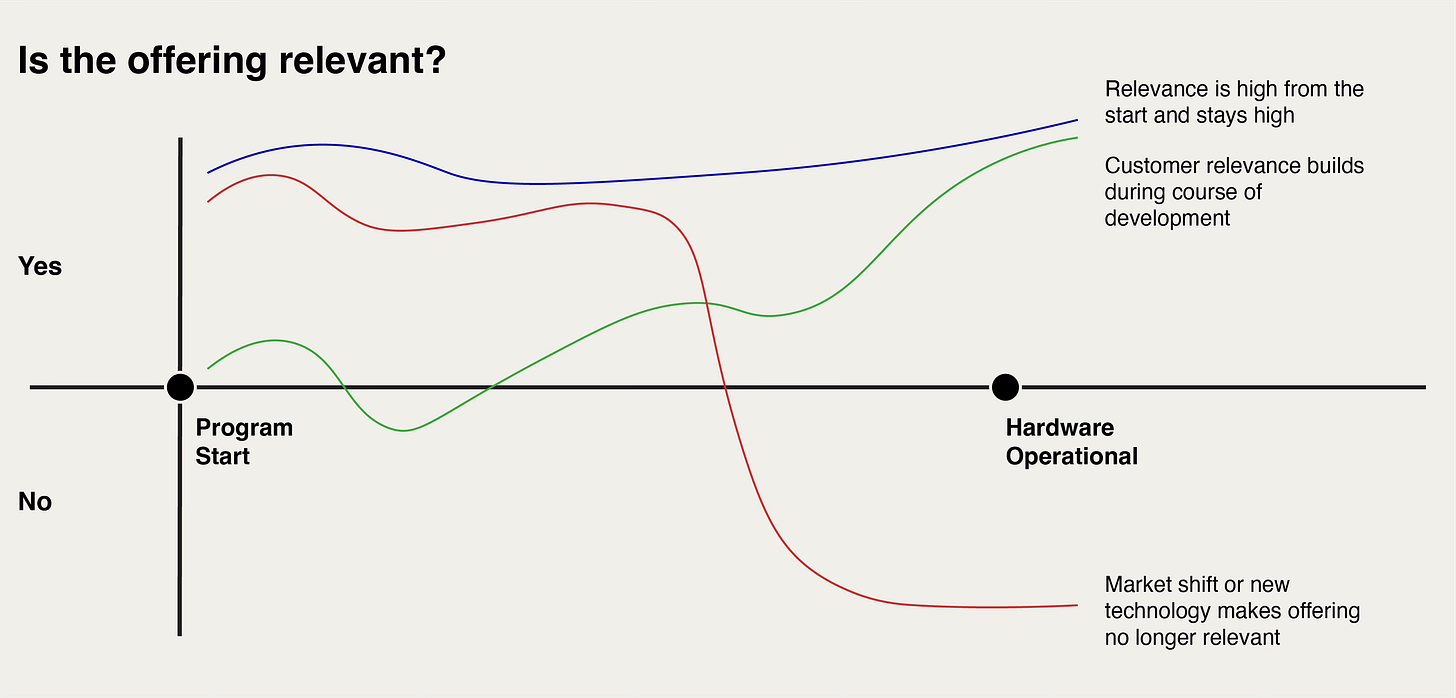

First, is our offering relevant? In other words, do customers want to buy what we’re selling? At the start of the project, hopefully the answer to this question is yes. If you waved a magic wand and the product appeared, there would be people waiting to use it.

However, maybe you’ve peered into the future and recognized that the market today doesn’t yet know what it needs. You’re betting that customer need will intensify—or emerge entirely—by the time you deliver.

Or, you’ll forge the fit yourself. Shape market expectations during development, educate customers on problems they don’t yet see, create demand where none exists today.

In the worst case, deep into your development program the offering becomes irrelevant. For example, the best Loran receivers became markedly less useful as GPS become more available (though they could be making a comeback).

Technology Stack

Is your technology stack state-of-the-art? Again, it most likely is at the beginning of the project. But your stack could take so long to develop that newer, more advanced technologies can emerge and maybe even mature faster.

I saw this happen with metallic 3D printed parts. When we started printing, Inconel 718 was the most mature high-performance alloy used for space-grade engine parts. But by the time the engines were developed, GrCop84, a copper alloy, had matured to the state-of-the-art. Just as printable, but higher performance.

We’d optimized our architecture around yesterday’s material.

Competitors

Do you have a durable advantage over your competitors? This might come in the form of team, technology, relationships, readiness or other moat.

If there are mature incumbents, you likely start with no advantage. You might have a potential edge—speed, technology, or cost structure—but that potential isn’t real yet.

In the best case, this advantage grows throughout your development program, hitting an all time high when you enter the market.

But new entrants that come behind you present a unique challenge: they’re shiny and new.

While you’re in year five—battle scarred from setbacks and delayed by regulatory hurdles—a new competitor launches with fresh funding and zero baggage. They haven’t accomplished much yet, but their unblemished story looks more attractive. Your hard won experience becomes indistinguishable from failure.

The longer you take to develop, the more vulnerable you become to someone starting the same journey with newer tools and a cleaner narrative.

Capital Markets

Is what you’re doing investable? This is a fundamentally different question than whether the technology works, or even if there’s customer demand.

At the most basic level, the potential value must justify the investment required, given total risk exposure. It also must look attractive on a relative basis. If an investor doesn’t invest in your company, but instead in another company doing something else (or similar), can they get a better return for less risk?

Entry point also matters. The price an investor buys at must be sufficiently low to achieve their target return. For early funds, this might be 25x or 50x. At the later stage, maybe 5x-10x. This creates a trap. Raise at too high a valuation early, and the company needs to grow into it before becoming investable again.

Additionally, general market cycles and sentiment matter. If public markets are at local lows when you fundraise, it’s a headwind (depending on the investor you’re targeting). If sentiment for your sector is high, you can ride the tailwind.

Regulatory Framework

Generally, regulatory frameworks are slow moving, if not fully static. This is both good and bad.

If the regulatory environment supports your business model at the onset, you’re in good shape. Unless something drastic happens, you should be okay by the time you come to market. And if something is going to change, you’ll see it coming over an extended period of time.

It’s not uncommon to seek regulatory changes during your development path, but it can add risk. For example, currently, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission takes 6-10 years to certify a new reactor. Their target for microreactors is 1.5-2 years, which is likely a key factor in many nuclear startups’ business models.

Political Will

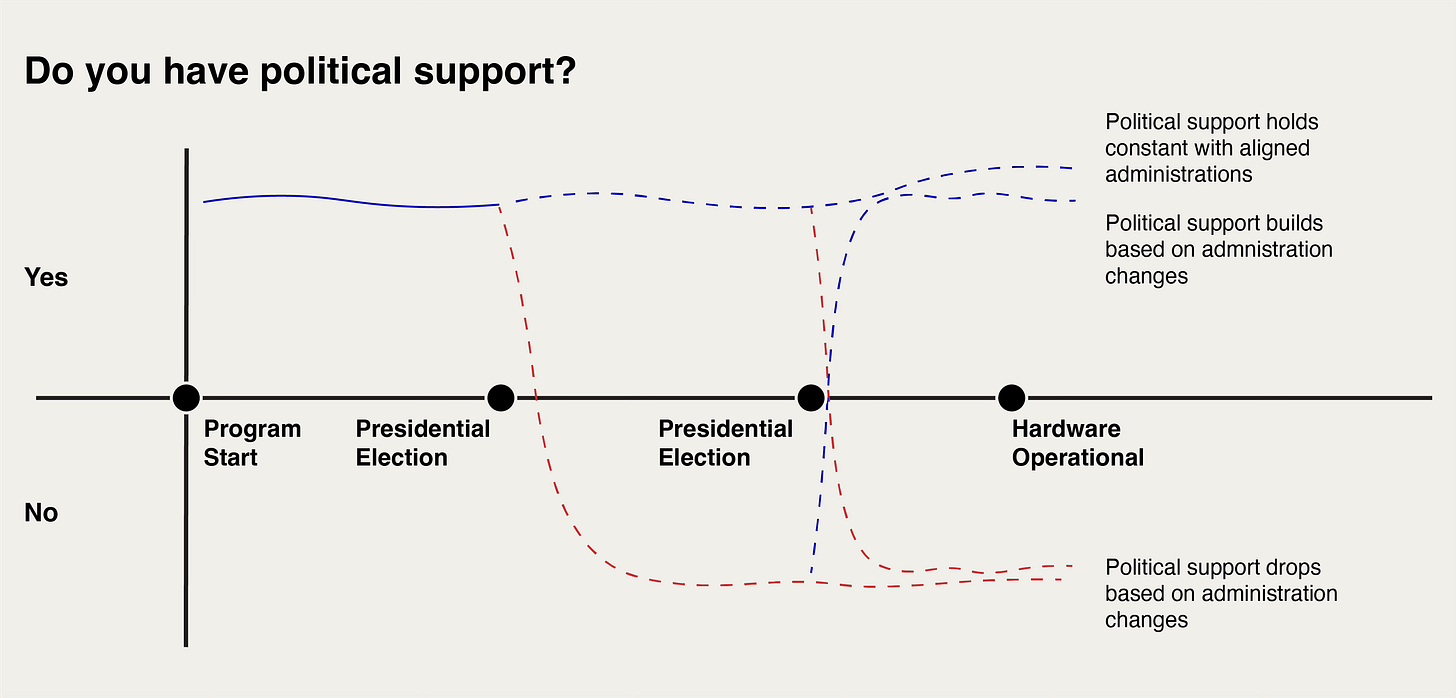

Separate from regulators, many high profile projects benefit from favorable political will. This can change every four years with different administrations. Projects that take longer than a single presidential term can face real political risk.

The higher profile and politically polarizing an endeavor is, the more care must be taken if the project is going to cross administration cycles. Further, it’s not possible to predict the next administration four years out. At best, insights can start to be drawn one year out from a potential shift.

For example, in the current administration, electric vehicle and renewable energy investments are more challenged than just eighteen months ago.

Public Support

Big projects live in public view. Rocket launches close beaches and roads. Nuclear reactors create safety risks—part perceived and part real. Factories create jobs.

All of these nudge the public’s perception of the program in different ways.

Public support operates as a force multiplier. Strong public backing accelerates permits, attracts talent, and provides political cover. Public opposition does the opposite—every milestone becomes a battle, every setback becomes ammunition, every delay compounds.

Public opinion forms early and hardens fast. A single early incident can define perception for years. Programs must invest in public trust from day one, not as an afterthought when opposition emerges.

The Composite Challenge

All of these alignment profiles combine into a composite curve of program market fit. It’s easiest to consider this qualitatively, as exactly how they combine mathematically isn’t straightforward.

Yet by mapping these cycles together, we can start to predict what the future might look like, when to time critical milestones, and whether we’ll have momentum when our product reaches market.

Moreover, these cycles don’t operate independently. They interact and amplify.

When capital markets turn bearish, investors scrutinize technology risk more harshly. When public opinion sours, political will evaporates. When new competitors emerge with shinier stories, customer excitement wanes. A misalignment in one dimension cascades into others.

The opportunity lies in seeing this clearly. While others react to each cycle independently, the best programs anticipate the interactions, time their moves to catch multiple tailwinds, and build resilience where headwinds are inevitable. They don’t just survive the cycles. They use them.