Designed in 36 days and Built for $10: How the Sten Gun Saved Britain

An example for modern defense production

Welcome to As Built! Today’s piece tells the story of the British Sten machine gun. I’ve always viewed this as the definition of both rapid development and design for manufacturing. The effort was motivated by the imminent threat of a German invasion, making it also a case study of how existential pressure drives extreme innovation.

Before we begin, a quick request. As Built is still young, and I’m working to grow awareness. I would be forever appreciative if you could share the blog with one person you think might find it interesting. Thanks so much, and I hope you enjoy!

The Sten gun exemplifies rapid engineering and design for manufacturing. With limited resources, this World War II era program accomplished what many modern defense production efforts strive to achieve. In about a month, British engineers created a low cost, mass producible weapon that would eventually arm millions.

The story offers many insights for modern efforts. But to truly understand how the British made this happen, we first need to contextualize the crisis that made it necessary.

Slow Beginnings

Britain’s involvement in what would become World War II began as a gradual diplomatic effort before a sharp inflection transformed it into a wartime crisis. The origin traced back to the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I. It was highly punitive, requiring Germany to disarm, pay reparations, and surrender territory.

As a result, Germany was forced to grapple with an extreme sense of defeat and humiliation. This was inherently destabilizing. Separately, political and social unrest presented across Europe, which was further exacerbated by a highly strained international economy. This led to the period between the world wars being unstable and insecure.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany and quickly began to rearm the country. While such development of the German military was prohibited under the Treaty of Versailles, the action drew relatively little international resistance. This set the stage for German territorial expansion.

In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Six months later, Hitler demanded possession of the Sudetenland, a border region of Czechoslovakia. Britain and France appeased and compelled Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland in an effort to achieve peace in Europe. Yet, in March 1939, Hitler violated this agreement and moved to occupy the rest of Czechoslovakia.

Alarms sounded across Europe, and Britain shifted its policy. In an attempt to curb German expansion, Britain and France provided security guarantees to Poland, which were promptly invoked. On September 1st, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Seven years of diplomacy had failed.

Phoney War

Britain deployed an expeditionary force to mainland Europe, but the war’s initial phase left observers bewildered. From September 1939 to May 1940, virtually no Allied military land operations occurred on the Western Front. There was so little military activity that this period became known as the “Phoney War.” Years of slow diplomacy gave way to slow battle.

In sharp contrast, at sea, German U-boats were active. Over the course of 1940, they would sink 563 ships in what was referred to as a “happy time” for the German submarine force. This prowess would later serve as a significant factor behind the Sten’s development.

Blitzkrieg Inflection

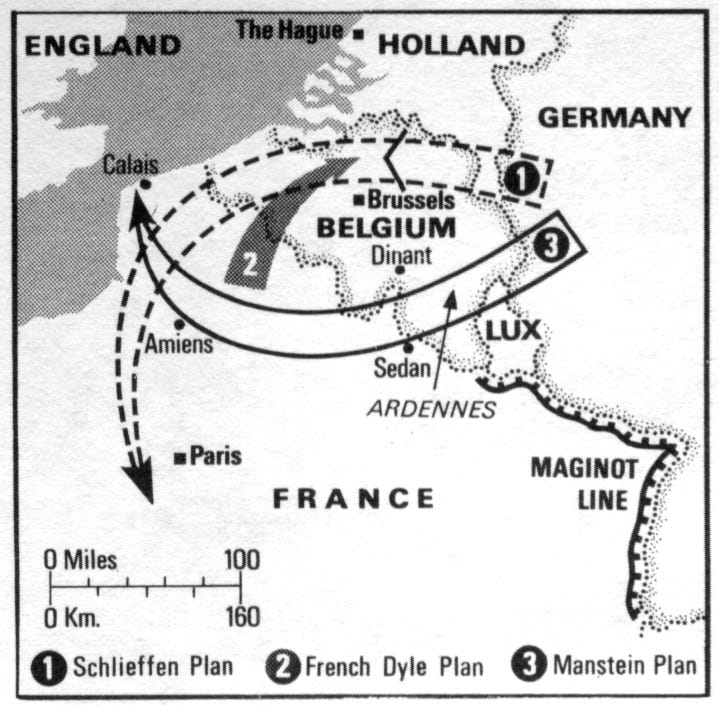

The slow Phoney War came to an abrupt end on May 10th, 1940. German troops, tanks, and aircraft poured into Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Within days, German forces advanced over a hundred miles. The Blitzkrieg — lightning war — had arrived in Western Europe with devastating effect.

The Allied response crumbled. Forces rushed north to meet what they expected would be the main German thrust through Belgium, as had happened in World War I. However, the German attack traversed the Ardennes Forest in southeastern Belgium and northern Luxembourg — terrain the French had previously considered impassable for armor. German tanks broke through French defensive lines and raced toward the coast.

Over the next two weeks, Allied forces were forced backwards at an astonishing rate. Quickly, the retreat turned catastrophic. British and French troops found themselves trapped against the English Channel. Rapidly advancing German forces led to the famous Dunkirk evacuation, where British civilians crossed the Channel to aid the Navy in rescuing the trapped soldiers.

Seven years of failed diplomacy had evolved into eight months of largely inactive war, which then collapsed into three weeks of devastating retreat. Britain was stunned.

Outgunned

While the May 1940 Dunkirk evacuation successfully rescued 338,000 Allied soldiers from the shores of France, most of their equipment was left behind. Britain lost an estimated 2,500 artillery pieces, 85,000 vehicles, 75,000 tons of ammunition, and thousands of machine guns on French beaches.

These equipment losses were only half the problem. Even before Dunkirk, British forces had been outgunned. Their bolt-action rifles were no match for German submachine guns that could deliver 500 rounds per minute. The British had neither the right weapons nor enough of them.

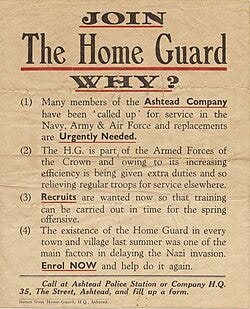

The German forces’ lightning speed, coupled with persistent air raids, made an invasion of Britain seem inevitable. Britain prepared by mobilizing 1.5 million volunteers into the Home Guard. Their first mission was to interfere with and slow down invading forces until the regular army could respond. Their second mission was to continue the resistance in the event of an occupation.

But while Britain was long on militia volunteers, it was short on weapons to arm them.

Three Bets

To address this problem, Britain launched three parallel efforts, which is itself a case study in parallel pathing and risk management.

Emergency Weapons

The first effort was to get weapons — any weapons — into soldiers’ hands. Britain pulled together about 300,000 Lee Enfield rifles and 59,000 Lewis guns from World War I stores. The regular army took most of the rifles, while the Home Guard received the Lewis guns, as well as about 50,000 shotguns collected from the civilian population. This approach had minimal cost and lead time, but the weapons were outdated and the quantities were relatively low.

Imports

Second, Britain bought whatever it could find. Canada sent 75,000 Ross Mark III rifles — a World War I era weapon that had been withdrawn from the front lines in 1916 for jamming. The United States sold 785,000 M1917 rifles and 108,000 Thompson submachine guns.

The Tommy guns were a step up in terms of technology, but this strategy was expensive and uncertain. At this point, each Tommy gun cost $4,600, and the total purchase topped $800 million, both in modern dollars. Notably, the Lend-Lease program had not yet been established, so this was a cash-and-carry deal structure, which drained British resources.

Even after the purchase, the weapons still had to cross the Atlantic, and this was the U-boat “happy time”. The German Navy was now operating from French ports, further extending its maritime dominance. Every shipment risked sending desperately needed weapons to the ocean floor.

Domestic Production

Third, Britain sought to develop its own weapons domestically. Some designs were in production, but they weren’t quite what was needed. For example, the Bren was a highly favored British machine gun that was developed throughout the late 1930s. It was reliable and accurate. But it was a large squad-level weapon, expensive, and required precision manufacturing. By the time of the Dunkirk evacuation, only about 30,000 had been produced, and the majority had been lost in France.

Britain needed something different: individual weapons for every soldier, rapidly mass produced at low cost. As the British Small Arms Committee framed the problem, “The most important consideration at the moment seems to be to get some form of machine carbine acceptable to all three services into production as quickly as possible.”

The first attempt was to reverse engineer and copy German weapons. The British designed the Lanchester submachine gun, which was a direct adaptation of the German MP 28. It was considered to be well made but required skilled craftsmen and precision parts. While cheaper than the Bren and the Tommy gun, it was still expensive. This was a step in the right direction, but still not quite what Britain needed.

36 Days to Save the Country

In December 1940, Lanchester manufacturing was scaling up at the Royal Small Arms Factory. There, a draftsman named Harold Turpin was supposed to be creating production drawings for the Lanchester gun.

However, he saw another way. Working after hours with Major Reginald Shepherd, a World War I veteran recalled from retirement, Turpin started sketching a different kind of weapon. Not better. Simpler.

The design philosophy was fundamentally different than other weapons programs. What if you designed a gun specifically for people who had never built guns before? What would the program look like with a focus on production over precision?

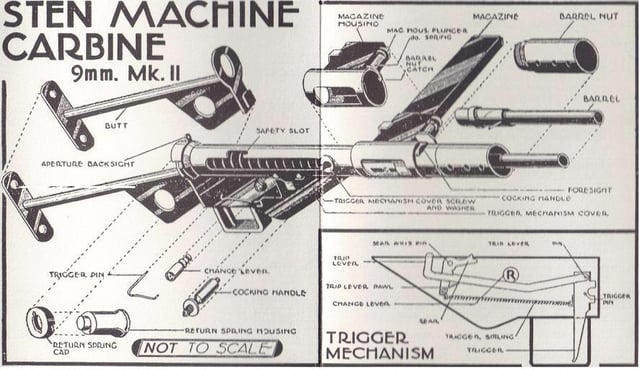

Turpin’s first insight came with the trigger mechanism. Where the Lanchester had complex machined parts, he designed a trigger that needed just two pieces of bent metal. This thinking spread to every component. The grip was a bent steel tube. The barrel’s protective shroud was made of stamped metal with holes cut into it.

By January 1941, just 36 days after starting, Turpin had built the first prototype. By many accounts, he made most of the parts himself. Some were even done in his home workshop. The weapon looked as if it had been assembled in someone’s garage, because, essentially, it had.

Looks aside, the Sten embodied three key design principles:

Minimal precision machining: Of the Sten’s 59 parts, only the bolt and barrel required precision work. Semi-skilled workers could stamp or weld everything else from stock metal. This eliminated the bottleneck of specialized machine tools and expert machinists.

Distributed, low infrastructure production: The simple components could be manufactured nearly anywhere. Britain set up production lines in converted furniture workshops, bicycle factories, and even private homes. Famously, the Tri-Ang toy factory was converted into a 24-hour Sten production line. Hundreds of small operations emerged across the country. Bomb one, and production continued elsewhere.

Widely available ammunition: The Sten fired 9mm rounds, the same ammunition used by German forces. This decision was strategic. Captured enemy ammunition could be used immediately, meaning resistance fighters across occupied Europe could resupply from German sources. This reduced the pressure to scale ammunition production.

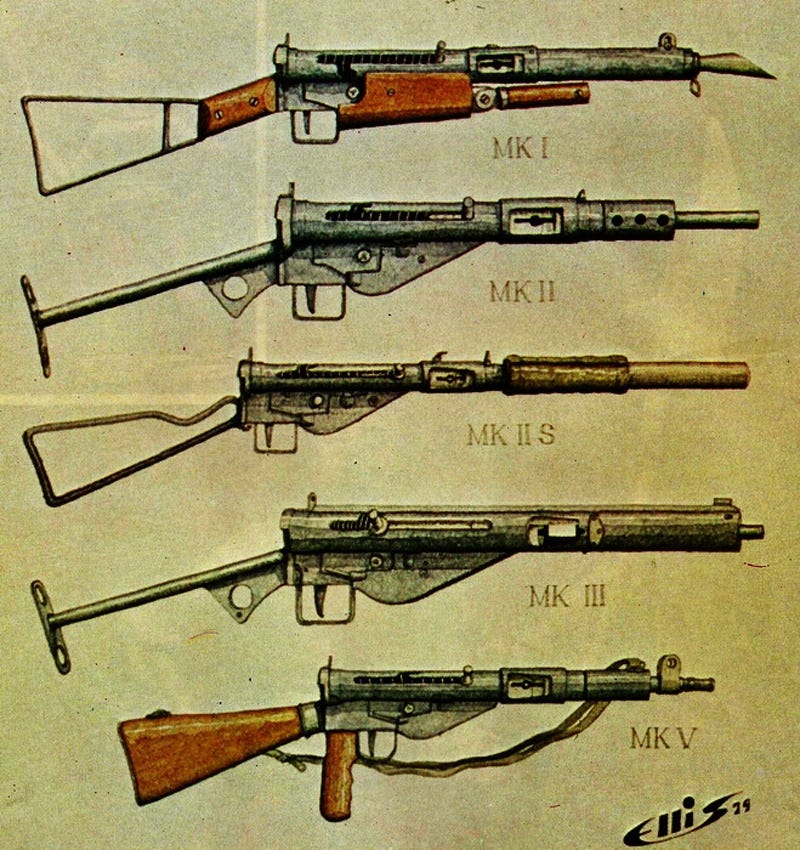

Throughout early 1941, Britain tested a variety of prototypes. By March, less than ten months after Dunkirk, they placed an order for 100,000 Sten guns. Yet, the designers kept simplifying. Version after version, they chopped every non-essential feature: flash hiders, wooden handguards, folding foregrips. If it didn’t help the gun shoot, it disappeared.

These decisions drove serious results. Eventually, the Sten could be built in five and a half hours and for $10 ( $220 in modern dollars). This was a stark contrast to the Tommy gun, which took days to make and cost thousands of dollars. Over the course of World War II, Britain would produce 4.5 million Stens.

The Gun They Could Build

The Sten delivered submachine gun capability at rifle-like prices and was churned out by the thousands in bicycle shops and furniture factories. By many measures, this was a success.

However, the design choices that enabled mass production created predictable problems. A simple blowback operation led to frequent jams. Minimal safety mechanisms caused accidental discharges. While easy to manufacture, the side-mounted magazine made handling awkward. Accuracy beyond 100 yards was negligible. Critiques vocally pointed all this out.

Yet, none of this mattered strategically. The Sten was designed for urban combat, resistance operations, and last ditch defense. Two factors matter in these scenarios. First, having a gun at all, and second, maximizing the volume of fire. The Sten checked both boxes.

High rate production also meant commanders could issue Stens more liberally than other weapons. Resistance groups across occupied Europe received them via airdrop. The weapon’s compatibility with captured German ammunition made it ideal for guerrilla operations behind enemy lines. Flaws existed, but in the calculus of total war, they were acceptable.

Decades of Service

Some of the most telling validation came decades later. While it was designed in 36 days as an emergency stopgap, the Sten remained in service with the British military until the 1960s and with other forces worldwide until the 1980s. The “proper” weapons it was meant to temporarily replace were retired decades earlier.

Britain’s 1940 crisis forced a fundamental question: do you want the best weapon or the weapon you can actually build? Britain did the latter, and they weren’t the last to face this choice.

Today, Ukraine is building drones in distributed Kyiv apartments using 3D printers and commercial components. At first, they crashed, were jammed, and had a limited range. However, Ukraine has built thousands of them while rapidly iterating on the technology. Now these systems have proven formidable against a better armed adversary.

The lesson of 1940 keeps teaching itself. In existential conflicts, given the resources on hand, the weapon you can build will always beat the weapon you can’t.

General References

“Treaty of Versailles - Reparations, Military, Limitations,” Encyclopædia Britannica, last updated August 26th, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Versailles-1919/German-reparations-and-military-limitations.

“Rearming Germany,” Facing History & Ourselves, accessed September 21st, 2025, https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/rearming-germany.

“Appeasement and ‘Peace for Our Time,’” The National WWII Museum, October 14th, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/appeasement-and-peace-our-time.

“Munich Agreement,” Encyclopædia Britannica, last updated July 20th, 1998, https://www.britannica.com/event/Munich-Agreement.

“Invasion of Poland, Fall 1939,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed September 21st, 2025, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/invasion-of-poland-fall-1939.

“How Europe Went To War In 1939,” Imperial War Museums, accessed September 21st, 2025, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-europe-went-to-war-in-1939.

“The Phoney War,” Legion Magazine, February 15th, 2020, https://legionmagazine.com/the-phoney-war/.

“Battle of France,” Encyclopædia Britannica, last updated May 10th, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-France-World-War-II.

“Blitzkrieg Explained,” Imperial War Museums, accessed September 21st, 2025, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/blitzkrieg-explained.

“Cheap Shot: How the Sten Gun Saved Britain,” HistoryNet, October 30th, 2019, https://www.historynet.com/cheap-shot-how-the-sten-gun-saved-britain/

“The Sten Gun, Its Name and the Men Behind It,” The Armourers Bench, May 18th, 2020, https://armourersbench.com/2020/05/17/the-sten-gun-its-name-and-the-men-behind-it/

“British Infantry Weapons of World War II,” Infantry Weapons, archived May 22nd, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20090522121134/http://infantry-weapons.org/smg_lmgs.htm

“Tri-ang: From Toys to Stens,” Royal Armouries, https://royalarmouries.org/objects-and-stories/stories/tri-ang-from-toys-to-stens

Carter, David M. “Sten Mk3: Britain’s Cheapest Submachine Gun of WWII.” Firearms News, August 1st, 2022. https://www.firearmsnews.com/editorial/sten-mk3-submachinegun-ww2/481344

McCollum, Ian. “British Submachine Gun Overview: Lanchester, Sten, Sterling, and More.” Forgotten Weapons, August 7th, 2014. https://www.forgottenweapons.com/british-submachine-gun-overview-lanchester-sten-sterling-and-more/

McCollum, Ian. “Sten MkIII: A Children’s Toy Company Makes SMGs.” Forgotten Weapons, April 4th, 2011. https://www.forgottenweapons.com/sten-mkiii-a-childrens-toy-company-makes-smgs/

Kay, Garry James. “The Weapon That Saved the British.” Recoil, April 10th, 2017. https://www.recoilweb.com/the-weapon-that-saved-the-british-106527.html

“Equipment the British Lost at Dunkirk that the Germans Reused,” Military Matters, September 14th, 2021, https://militarymatters.online/military-history/equipment-the-british-lost-at-dunkirk-that-the-germans-reused/

“US Aid For The WW2 British Home Guard,” M. Watkin, accessed December 2024, https://www.mwatkin.com/us-aid-to-britain

“Money & Guns in WWII, the Cost of SMGs and Sidearms,” War History Online, April 24th, 2019, https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/money-and-guns-in-wwii.html

“Ship losses by month,” Uboat.net, https://uboat.net/allies/merchants/losses_year.html

“Wartime Changes: The Bren MkI Modified and Bren MkII,” Forgotten Weapons, https://www.forgottenweapons.com/wartime-changes-the-bren-mki-modified-and-bren-mkii/

“Ugly But Effective: How the Sten Gun Became a WWII Workhorse,” ITS Tactical, May 7th, 2018, https://www.itstactical.com/warcom/firearms/ugly-but-effective-why-the-sten-gun-became-a-wwii-workhorse/

“The Sten - Meet the $10 Submachine Gun That Helped the Allies Win WW2,” MilitaryHistoryNow.com, May 3rd, 2018, https://militaryhistorynow.com/2013/12/09/the-venerable-sten-britains-10-dollar-submachine-gun/

“How the STEN Submachine Gun Helped the British Army During WWII,” War History Online, October 31st, 2022, https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/sten-submachine-gun-british-army-wwii.html