Happy New Year! Kicking off the 2026 As Built series with one more engineering piece. In this case, a look at systems explicitly designed for when things aren't going as planned. Coming up, the next few essays in the pipeline are all space related. Enjoy!

It’s October 1944. A P-51 pilot over Europe spots a German Bf 109 fighter on his tail. He shoves the throttle forward, past the stop, and through the safety wire. As the wire snaps, engine power surges from 1,490 to 1,720 horsepower. He races away from danger, but has just a few minutes before the Merlin engine starts eating itself.

That broken wire represents a fundamental engineering reality: nominal systems fail in off-nominal conditions.

The most trustworthy designs don’t just meet the spec, they hold reserve capacity for moments when the spec becomes irrelevant. This reserve isn’t free. Its cost comes in weight, complexity, maintenance, and money. But it’s the difference between a system that survives the unexpected and one that doesn’t.

Three examples — spanning 80 years and three different failure modes — show how high performance systems can be built for the moments when everything goes wrong.

War Emergency Power

In WWII, engine power decided dogfights. More meant a pilot could outmaneuver or outrun the enemy. But what happens when a pilot encounters a threat while already at full throttle? Or stumbles across the enemy’s latest fighter with a bigger engine and higher top speed?

For these situations, American engineers created War Emergency Power.

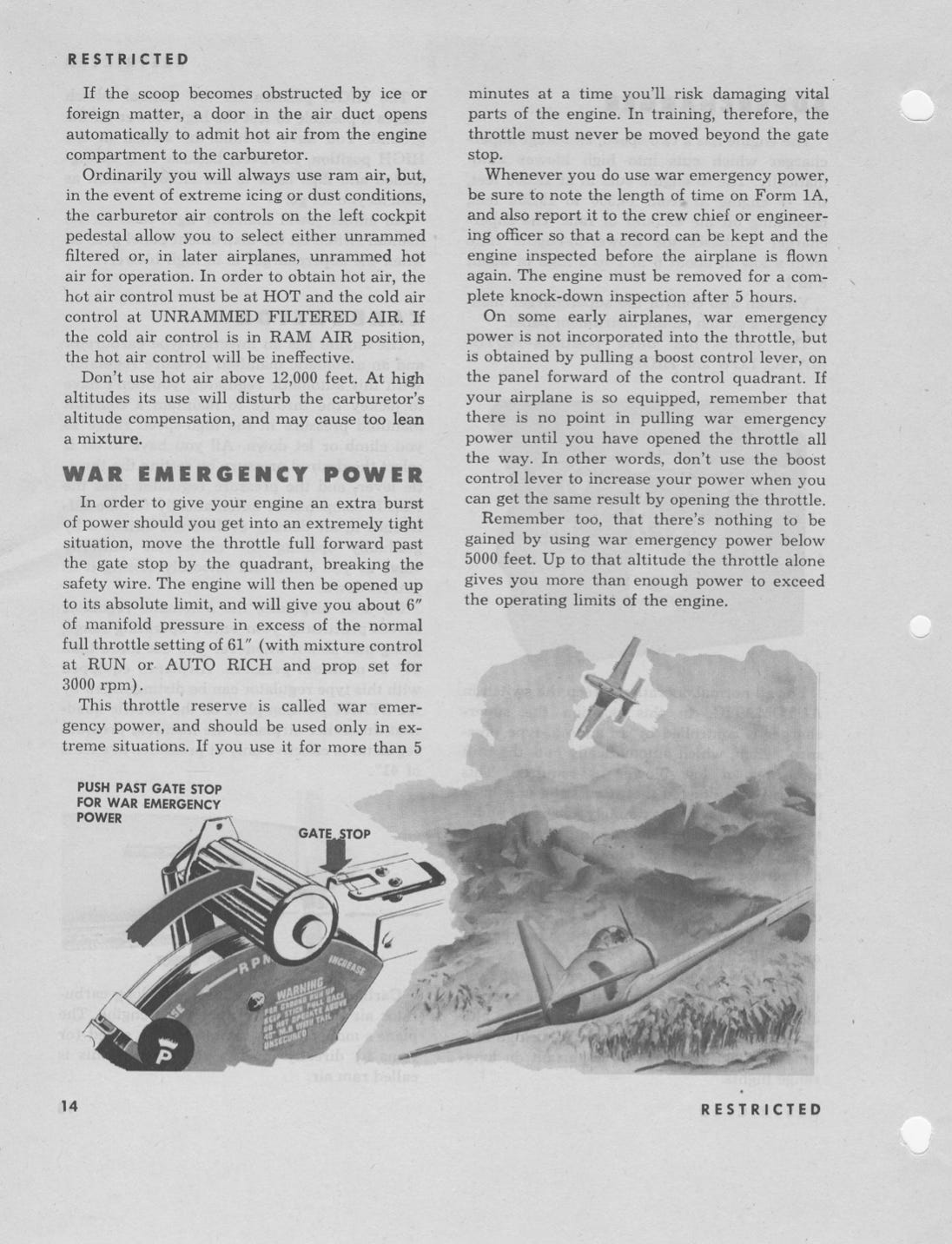

WEP was a throttle setting beyond 100% of rated power. The throttle interface guarded the activation of this setting. Safety wire across a gate stop physically prevented the throttle lever from advancing. To access WEP, pilots had to sever the wire.

There was symbolism in this action. You were breaking something to get this power.

Boosting power meant cramming more air and fuel into each cylinder. But the challenge was detonation.

In a properly running engine, the spark plug ignites the fuel–air mixture, and a flame front propagates smoothly along the combustion chamber. Detonation occurs when the unburned mixture ahead of the flame front auto-ignites due to excessive heat and pressure.

This causes an extremely rapid pressure rise and shock waves within the cylinder, which can crack pistons and bend connecting rods. Pilots and auto enthusiasts know the tell-tale sound: engine knock.

The simplest way to boost was just opening the throttle wider, cramming more air into cylinders already running hot. This worked, but pushed the engine closer to detonation.

Injecting a water-methanol solution into the supercharger intake offered a clever solution. The water absorbed heat as it evaporated, cooling the intake charge and making it denser. This enabled more oxygen per cylinder. The methanol raised the fuel’s effective octane rating and also provided some cooling. Together, these effects raised the detonation threshold.

The U.S. military continuously developed this approach throughout WWII. By the time the P-51H took flight, WEP boosted power from 1,380 HP to 2,218 HP, an astounding 60% increase.

The Germans did the same with their MW 50 (Methanol Wasser 50) system. It could push a BMW 801 engine from 1,600 HP up past 2,000 HP.

They also fielded the GM-1 (Göring Mischung 1) system for high-altitude operations, where thin air starved engines of oxygen. This system injected liquid nitrous oxide directly into the supercharger intake. As the nitrous oxide decomposed in the heat, it released oxygen, chemically enriching the mixture where the atmosphere couldn’t.

The trade-off was explicit. Activating WEP triggered enhanced inspections and often a complete engine teardown. Technicians pulled the Merlin apart, looking for cracked pistons, scored cylinders, and damaged bearings. Every second of emergency power consumed engine life at a far accelerated rate.

But the designers weren’t trying to build a sustainable system. They were buying pilots a way out. The wire existed so that the cost of using it was clear. But if breaking a wire meant surviving, it was an obvious trade.

Takeoff Contingency Power

Thirty years later, a similar principle appeared in a very different context. The Concorde carried 100 passengers at Mach 2, powered by four Olympus 593 turbojets. These engines each had a maximum continuous thrust of 28,800 lbf, which generated 736°C exhaust gas. At this power, the engines could run continuously for an unrestricted duration.

As with any aircraft, one of the most dangerous scenarios was losing an engine during takeoff. At this point, the plane was at maximum weight, minimum speed, and had no altitude to trade. With few options, this required a different kind of margin.

The Olympus 593 had two thrust ratings that mattered here: takeoff power and contingency power.

Takeoff power with reheat on (afterburners) generated 37,080 lbf. This was already 28% higher than cruise thrust and drove exhaust gas temperatures to 806°C. Under these conditions, the maximum duration was five minutes.

Contingency power pushed harder still.

This setting existed solely for engine-out scenarios during the takeoff roll. It drove the engines to 38,130 lbf and an exhaust gas temperature of 883 °C. At this pace, the engines had just two and a half minutes before thermal limits became structural limits.

Activation was automatic. When an engine’s N2 — the rotational speed of its high-pressure compressor — fell below 58.6 percent, the system reacted automatically. The takeoff monitor throttled the remaining engines up to contingency power to compensate. The pilots didn’t break a wire. The system detected and responded on its own.

This automation reflected a shift in how engineers thought about off-nominal operations. WEP assumed a pilot making tactical decisions under fire. Concorde’s contingency power assumed a crew managing a crisis with passengers aboard. The cognitive load had to stay low, and the response had to be immediate.

The trade was time-limited by thermal margins. The material selection in the Olympus 593 engines was tailored to handle high temperatures. Yet, at 883°C, the exhaust gas caused many engine parts to approach material limits.

Two and a half minutes were enough to clear the runway, establish a climb, and retract the gear. But they had to be done quickly and deliberately. The system provided immediate survival, not extended comfort.

In Flight Abort

Jumping ahead to modern day, the SpaceX Dragon capsule is the primary ride to space for U.S. astronauts. The vehicle carries two propulsion systems: Draco and SuperDraco. Both use monomethylhydrazine (MMH) and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO), which are hypergolic propellants. They combust on contact, with no spark required, making them highly reliable.

The sixteen Draco thrusters handle orbital maneuvering, with each generating 90 pounds of thrust. They’re designed for long-duration operations: attitude control, orbit adjustments, and deorbit burns.

The SuperDracos exist for a different purpose entirely. Eight engines are built into the capsule’s sidewalls, with each producing 16,000 pounds of thrust. All are oriented facing aft and together generate 128,000 pounds of thrust.

If the Falcon 9 beneath fails, the SuperDracos fire and accelerate Dragon away at about four g’s. The burn lasts roughly five seconds. In this time, the capsule travels nearly a mile, which is enough separation to be survivable. Once clear, Dragon’s trunk separates, the capsule reorients, and parachutes deploy.

Here, the engineering achievement wasn’t just in the engines, it was also in how they integrated into the vehicle.

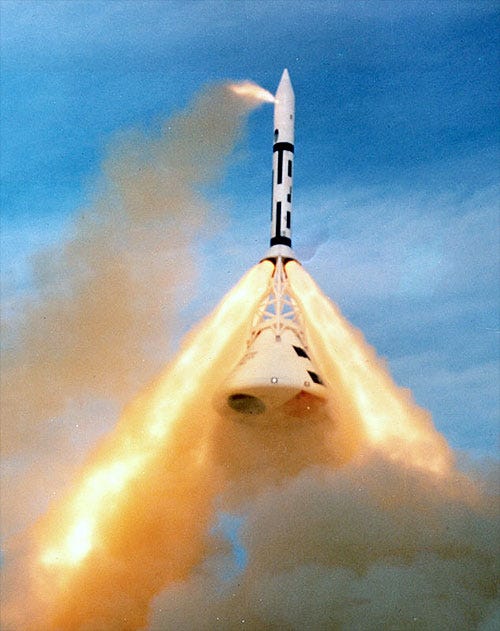

Traditional launch escape systems on Mercury, Apollo, and Soyuz used solid-fuel towers mounted ahead of the capsule. They worked, but often had to be jettisoned partway through ascent because the tower’s aerodynamic fairing hit limits. This created blackout zones during ascent when the abort system was gone, but the rocket could still fail. In this window, the crew was unprotected.

Dragon’s integrated approach eliminates blackout zones. The SuperDracos are part of the capsule structure, not a jettisoned tower. The abort system remains continuously active from the pad straight through to orbit.

The time scales here are different from anything that came before. WEP gave pilots five minutes of emergency power before the engine needed a teardown. Concorde’s contingency rating allowed 2.5 minutes at elevated thrust. Both assumed human operators would recognize the problem, make a decision, and take action.

SuperDraco operates faster than human cognition. The transient from ignition to full thrust is 100 milliseconds. The system monitors Falcon 9 telemetry and, if parameters exceed limits, automatically fires. The entire chain of fault detection to separation happens faster than a pilot could process something going wrong.

Dragon carries the entire SuperDraco system purely for emergency off-nominal scenarios. At one point, SuperDracos were meant to double as propulsive landing engines. SpaceX dropped that in 2017, though recent filings suggest it may return for contingency landings. But generally, during a good mission, the system is never activated.

The SuperDraco system adds mass, complexity, and cost to every mission. But when you’re sitting on a million pounds of propellant, it’s the only way out.

The Trade

Every off-nominal system is a bet about which components you can afford to lose.

WEP destroyed engines. Concorde’s contingency rating shortened the time between overhauls. Dragon’s SuperDracos add mass to every mission. None of these reserves is free. They represent decisions to accept penalties during normal operation in exchange for capability in extraordinary times.

This is the hardest kind of engineering: paying every day for something you hope never to use.

Such systems are easy to cut. They add cost without adding capability — until the day they’re the only capability that matters. When written down and considered in detail, the value is obvious. Yet in design reviews, someone always asks: do we really need this margin? Every flight where the reserve goes unused looks like evidence that it wasn’t needed.

This works until it doesn’t.

The P-51 pilots, Concorde crews, and Dragon astronauts all know. When the failure cascade starts, reserve capacity is the only margin that matters.

Photo Credits

P-51 Throttle Quadrant / WEP Diagram: U.S. Army Air Forces, Pilot Training Manual for the P-51 Mustang (AAF Manual 51-127-5), 1945. Public Domain, via t6harvard.com

P-51 Mustang: Courtesy of To Fly and Fight / CE “Bud” Anderson (toflyandfight.com)

Concorde at Mach 2: Adrian Meredith / Royal Air Force, via PetaPixel

Olympus 593 Engine: Heritage Concorde (heritageconcorde.com)

SpaceX Draco and SuperDraco: SpaceX, via Spaceflight Now and SpaceNews

Apollo Launch Escape System: NASA