Most explainers treat satellite orbits as altitude bands. LEO, MEO, and GEO are likened to floors in a building. Low is close. High is far. Pick your level.

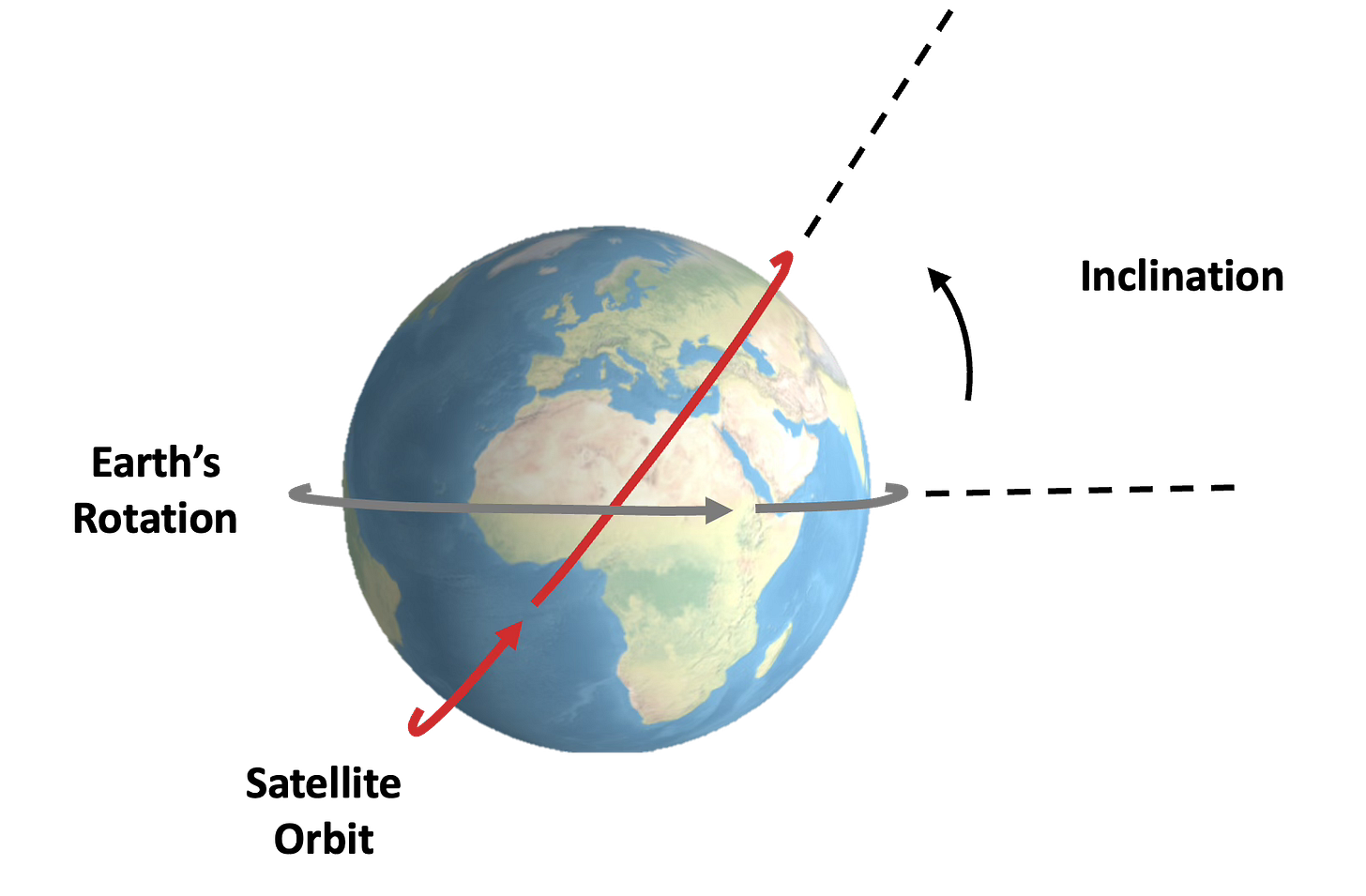

But altitude is just one of many variables that define an orbit. Inclination, eccentricity, and period matter just as much. Two satellites at the same altitude can have completely different capabilities depending on how their orbits are tilted and shaped.

Instead of points on a map, orbits can be thought of as mission enablers. Each buys you a specific advantage, such as persistence, proximity, global access, or stability. Depending on what you’re trying to achieve, you can tailor the orbit to your mission.

Each comes with costs, too. Some orbits are hard to get to, while others are difficult to maintain. A few are prime real estate and get crowded.

The question isn’t just where to orbit. It’s what advantage do you need?

Persistence

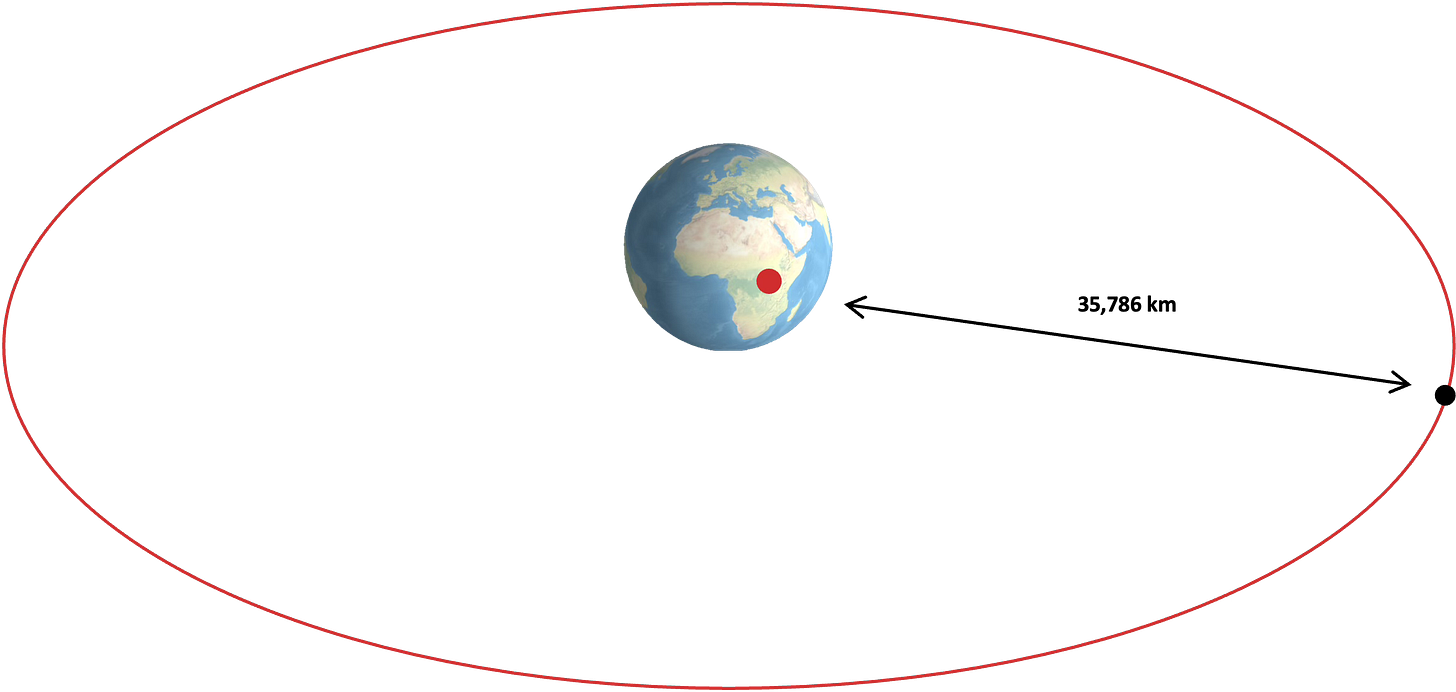

A satellite above the equator at an altitude of 35,786 km circles the Earth at the same rate as the Earth’s rotation. It therefore hangs over one spot on Earth, earning it the name geostationary or GEO.

From this geostationary vantage, the satellite can see about 40% of Earth’s surface. But its usefulness degrades toward the edges of its field of view, where the satellite drops to roughly 5° to 10° above the horizon. Signals must pass through substantial atmosphere and are easily blocked by terrain and buildings. This makes GEO satellites less effective at servicing high latitudes.

But within the effective footprint, there are no handoffs, gaps, or timing windows. This creates a persistence advantage.

NOAA’s GOES (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite) weather satellites stare at the same hemisphere permanently, watching hurricanes develop in real time. Many missile warning systems need unblinking eyes over potential launch sites. Broadcast TV uses GEO because a fixed satellite enables fixed dish antennas, which are simple and cheap.

The cost is distance. Signal latency is about 240 milliseconds for round trip propagation, but around 500 to 600 milliseconds once you account for routing and processing. That’s noticeable in voice calls and painful for real-time applications.

Getting there is also expensive. As we’ll see below, orbital mechanics demands significant energy to get to GEO, which first requires traversing the geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO), a Hohmann transfer as outlined below.

For small launchers, this orbit is often unachievable. For most larger rockets, the payload to GTO or GEO is a fraction of that to LEO. It’s often on the order of 30% to 40% to GTO, and lower to true GEO depending on the mission.

And the equatorial GEO belt has limited slots. Only so many satellites can park at useful longitudes before they start interfering with each other, making an orbital slot at this location a valued asset.

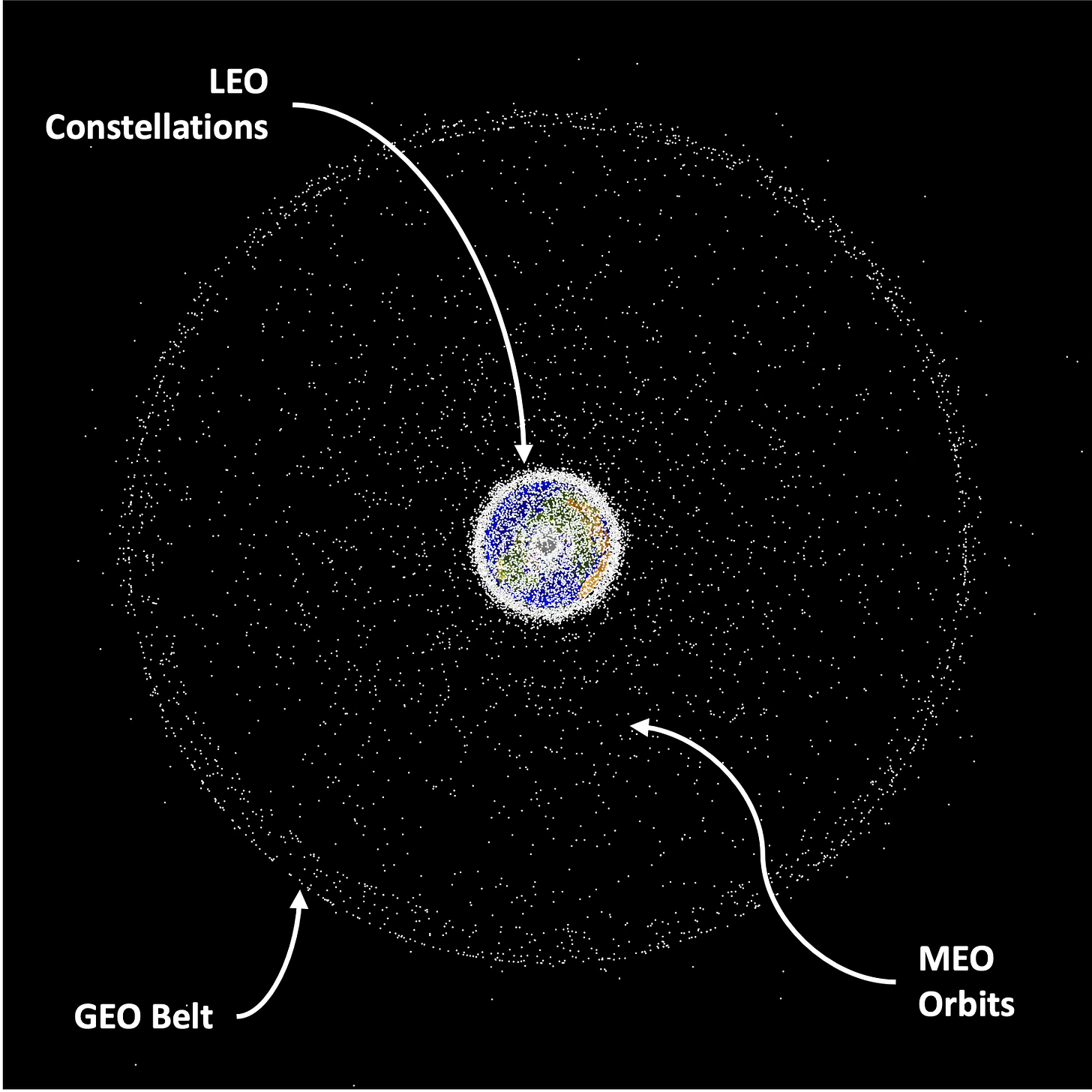

The image above is from NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office and illustrates satellites in orbit from 2019, as seen from a viewpoint above the north pole. The well-populated equatorial GEO belt can be clearly observed, as well as the LEO and MEO orbital densities.

To expand on GEO, we can add inclination by tilting the orbit at an angle relative to the equator. Few satellites, except for those in GEO, orbit at 0° (equatorial) inclination. Most have some inclination to modify their ground track.

If you maintain the geosynchronous daily orbital period, but add inclination (and/or eccentricity), the satellite becomes geosynchronous (GSO) rather than geostationary (GEO). It no longer stays fixed. Instead, its ground track becomes an analemma (figure eight).

The relatively concentrated ground track is still useful, and we’ll see it deployed below for Tundra orbits.

Proximity

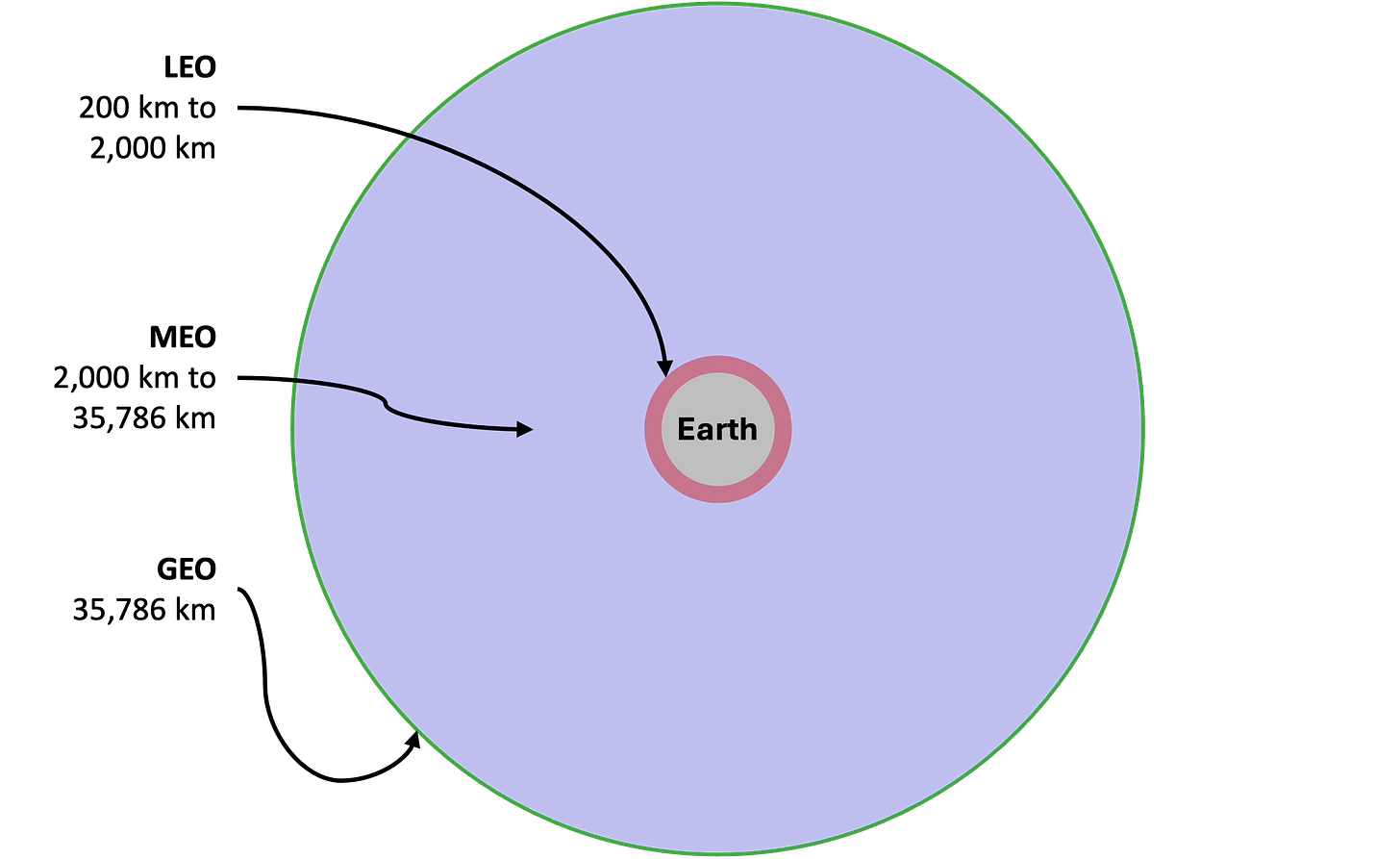

Low Earth orbit (LEO) offers the opposite advantage: closeness. Technically defined as 200 km to 2000 km, LEO is often most concentrated around 400 km to 600 km. At this altitude, a lap around the Earth takes about 90 minutes.

Here, you’re near the action. Round trip latency drops to 10 to 40 milliseconds. Imaging resolution improves dramatically. The closer you are, the smaller the objects you can resolve. Higher signal strength allows user terminals to be smaller and cheaper.

This makes LEO popular. SpaceX and Amazon operate megaconstellations for global satellite broadband here. As a point of reference, SpaceX’s Starlink constellation has just under 10,000 satellites in orbit, and Amazon is targeting a 3,000+ deployment.

Besides the telecom megaconstellations, the International Space Station orbits at 400 km, and many imaging and remote-sensing constellations fly at similar altitudes.

Here, the cost is the coverage footprint. A LEO satellite at 500 km sees only about 1-2% of Earth’s surface at a useful angle. This necessitates constant handoffs and complex coordination between orbiting satellites. Global coverage requires hundreds or thousands of satellites, usually in mid-inclination orbits of 30° to 60°.

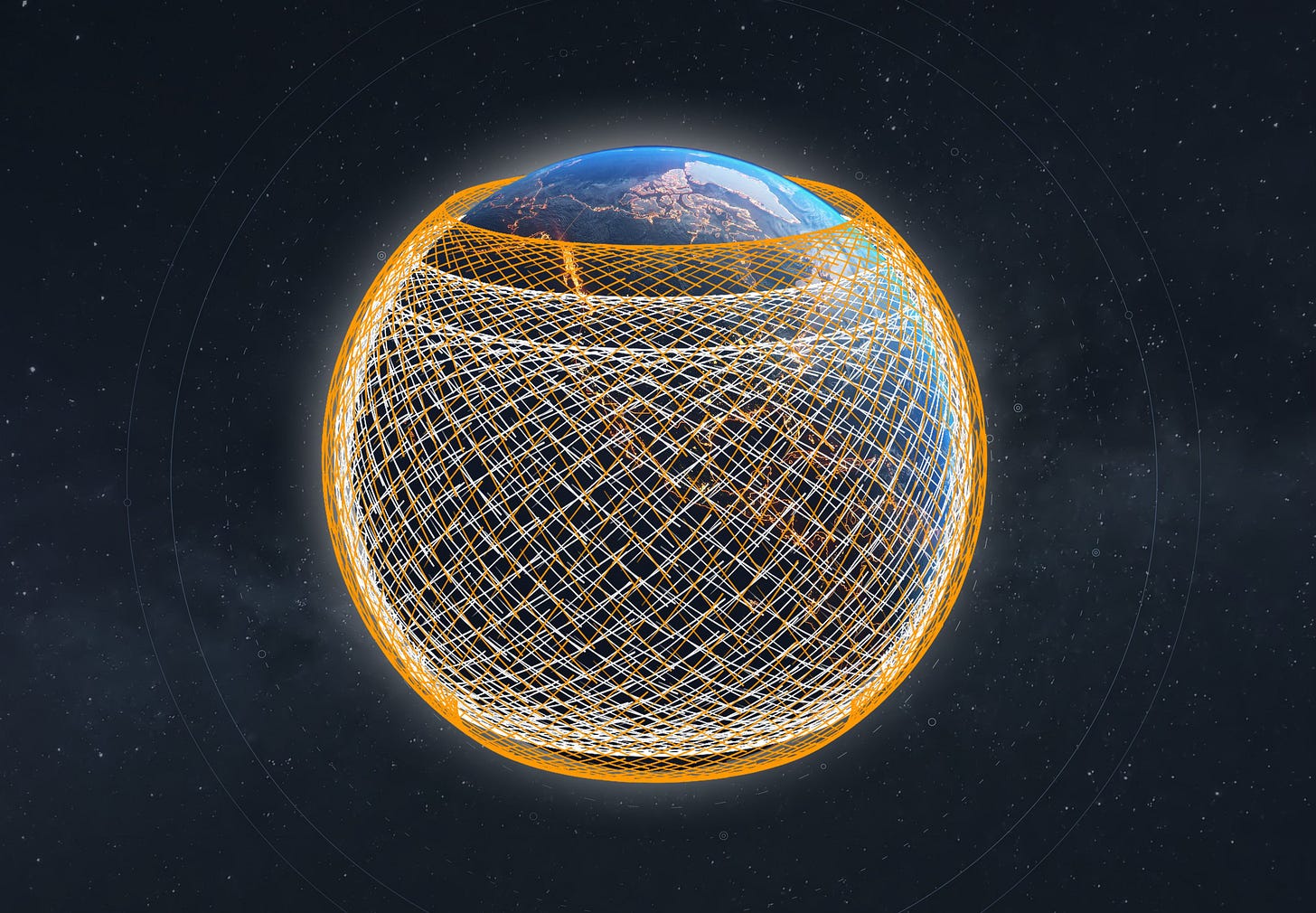

This arrangement provides good coverage over populated areas, but not at high latitudes. Amazon’s megaconstellation below illustrates the limited coverage near the poles for an inclined LEO constellation.

At the lower end of the LEO altitude range, atmospheric drag is also a real factor. This eats away at a satellite’s velocity. Without periodic reboosting, satellites can fall out of orbit. Even with propulsion, many LEO platforms plan for lifetimes ranging in the single digits of years.

Proximity gets you close. But staying close takes work.

Balance

Medium Earth orbit — roughly 2,000 to 35,786 km — splits the difference between LEO and GEO.

For example, at 20,200 km, you’re high enough that each satellite sees about a quarter of Earth’s surface, but low enough for reasonable latency and signal strength. This is the GPS altitude. The constellation’s 31 satellites can cover the entire globe, and the geometry works for precise positioning because multiple satellites are always visible from any point on Earth.

Similarly, SES operates a communication constellation at 8,000 km. The pitch is high bandwidth with tolerable latency. It’s better than GEO’s delay, but simpler than LEO’s thousands of satellites and constant handoffs.

The downside is that MEO doesn’t necessarily optimize anything. It’s not as persistent as GEO, not as close as LEO. MEO is capable and flexible, but rarely the best choice for any single parameter.

Global Access

Maybe you want access — the ability to see anywhere and everywhere. Polar orbits help with this.

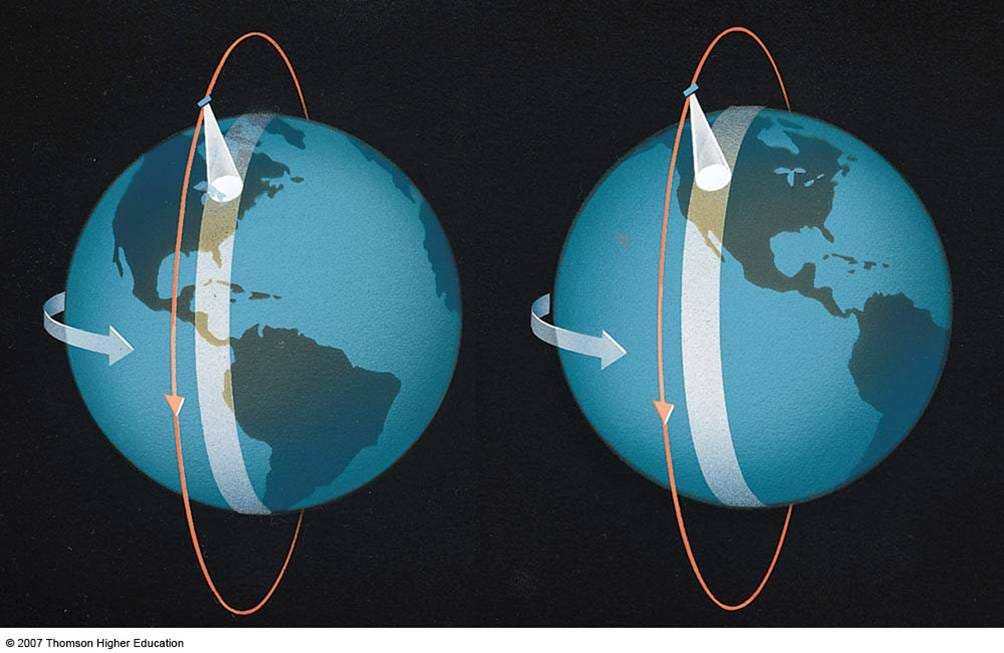

A polar orbit passes over both poles. In other words, the satellite circles the Earth from north to south. As Earth rotates beneath, each successive pass covers a new strip of ground. Wait long enough, and you’ve seen everything.

The advantage here is that nothing hides. The National Reconnaissance Office doesn’t need to choose which territory matters. Polar orbits give access to everything. Denied airspace, hostile nations, and polar regions are all within reach.

This fact is perhaps best embodied by the NRO’s Octopus emblazoned mission patches.

There’s also a tactical trick available. At the poles, all longitude lines converge. This means a small propulsive maneuver at the poles can shift subsequent ground tracks by hundreds of kilometers.

Satellites can be quickly readjusted to focus on emerging conflicts or areas of interest. Inclined orbits can’t do this easily; their ground tracks are constrained by geometry. Need to overfly a different target on the next orbit? Burn at the pole.

The cost is launch efficiency. An equatorial launch to the east gets a 460 m/s boost from Earth’s rotation. That’s about 5% of orbital velocity for free.

In practice, most missions launch from higher latitudes, such as 28.5° for Cape Canaveral, and go into mid-inclination orbits. This reduces the boost, but it still helps.

A polar launch from Vandenberg doesn’t get this benefit, as you’re launching nearly perpendicular to Earth’s rotation. As a result, the rocket has to supply all the orbital velocity, meaning polar access costs more propellant than equatorial orbits.

But for reconnaissance, global reach justifies the launch cost.

Static images only go so far in visualizing all the different orbits. NASA created a fantastic orbital fly-through video that illustrates the many dimensions of the satellites orbiting Earth.

High Latitude Loiter

The Soviet Union couldn’t use GEO effectively. Their territory stretches across high latitudes — 60°N and above — where geostationary satellites sit low on the horizon. Buildings block the signal. Terrain creates shadows. Trees get in the way.

They also lacked equatorial launch sites, making GEO expensive to reach from Baikonur.

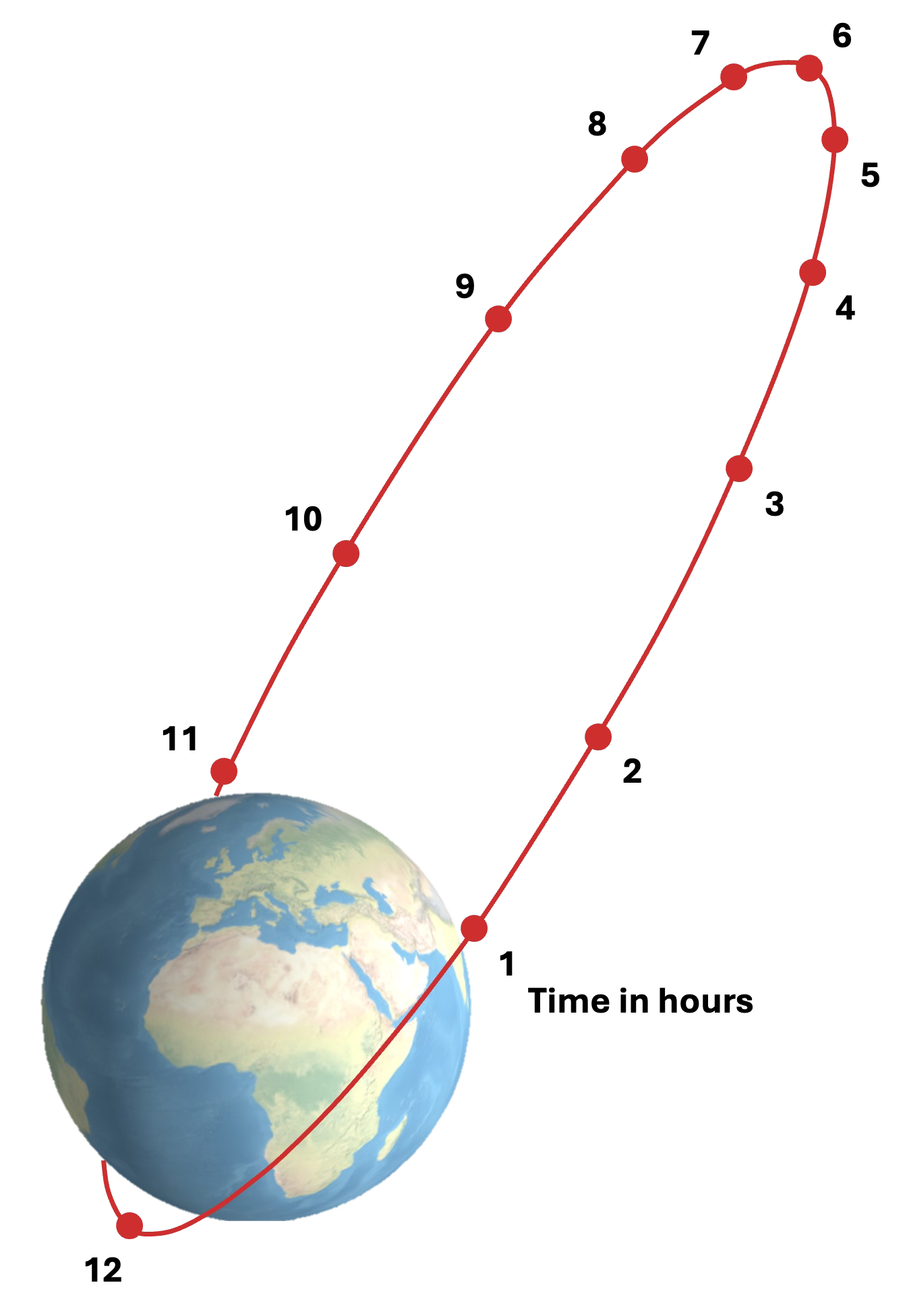

The solution was Molniya orbits. These are highly elliptical paths with perigee around 500 km and apogee near the GEO radius. A satellite in this orbit screams through perigee in minutes but loiters around apogee for eight-plus hours. It hangs nearly stationary over high-latitude regions.

Molniya’s 63.4° inclination builds further advantage.

Earth is not a perfect sphere. It’s slightly squashed, with extra mass around the equator. That bulge pulls unevenly on an inclined, elliptical orbit, creating a steady twisting force that rotates the ellipse in space. The line connecting perigee and apogee slowly turns.

At 63.4° inclination, that twisting cancels out, and the torque sums to zero. The orbit still precesses in other ways, but the ellipse itself stops rotating. Apogee stays fixed relative to Earth.

From Moscow, the satellite appears to hover nearly overhead.

The cost is numbers. A single Molniya satellite only loiters for part of its orbit. Continuous coverage requires at least three spacecraft orbiting in relay.

Yet, three Molniyas beat zero GEOs.

Tundra orbits work similarly. The satellite traces a figure-eight pattern over the ground but spends most of its time over the target region.

Sirius XM originally used three satellites in geosynchronous Tundra orbits to serve North America. This keeps at least one satellite high in the sky at all times, which is critical for car radios that need a clear line of sight through windshields.

Consistent Lighting

Earth observation satellites need to compare images over time. Is the forest shrinking? Is the city growing? Did those trucks move?

This only works if the lighting is consistent. Shadows must fall the same way in January and July, morning and afternoon. Otherwise, you’re measuring sun angle, not ground truth.

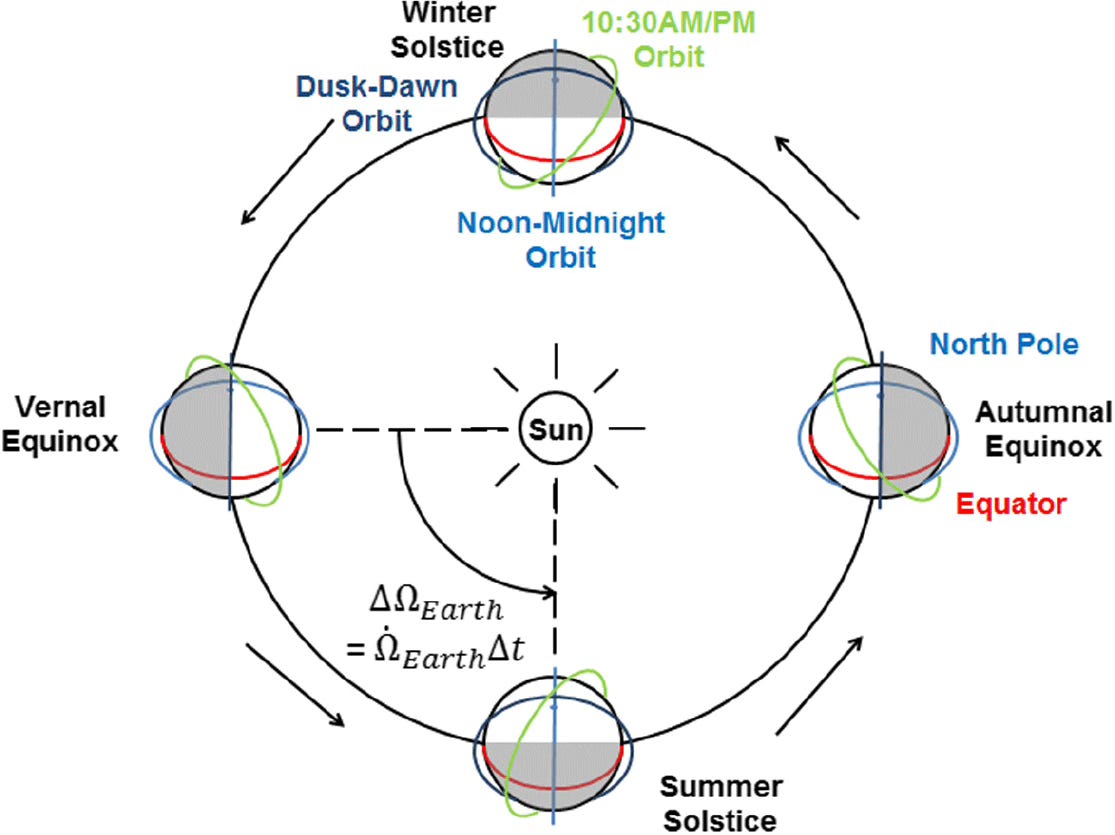

Sun-synchronous orbits solve this. They exploit Earth’s equatorial bulge — the J2 perturbation to be specific — to precess the orbital plane at exactly the rate Earth orbits the sun. The result is that the satellite crosses every latitude at the same local solar time, every day, year-round.

The choice of local time depends on the mission. Mid-morning orbits around 10:30 AM balance illumination and shadow. They’re ideal for optical imagery where terrain contrast matters. Dawn-dusk orbits ride the terminator, keeping solar panels in near-constant sunlight and minimizing eclipses. Radar satellites love this. Noon orbits maximize brightness but flatten everything.

Landsat, the longest-running Earth imagery program, has used sun-synchronous orbits since 1972. Planet Labs relies on this orbit for modern commercial imagery. SSO is also popular among reconnaissance satellites focused on change detection. Consistent lighting is the advantage that makes comparison meaningful.

The physics requires an inclination of about 98° between 600 km and 800 km. That’s slightly retrograde, meaning the satellite actually orbits westward against Earth’s spin. You lose the rotation boost at launch and also pay a small penalty on top.

The Transfer Problem

Orbits are commitments. They are expensive to reach and difficult to change once you’re there.

When we think about adjusting an orbit, there’s raising the altitude and changing the inclination. Both cost delta-v — velocity change — and satellites carry limited fuel to perform such a maneuver.

Reaching LEO from Earth’s surface takes roughly 9.4 km/s. This factors in 7.8 km/s of orbital velocity and about 1.4 km/s to overcome gravity and aerodynamic losses.

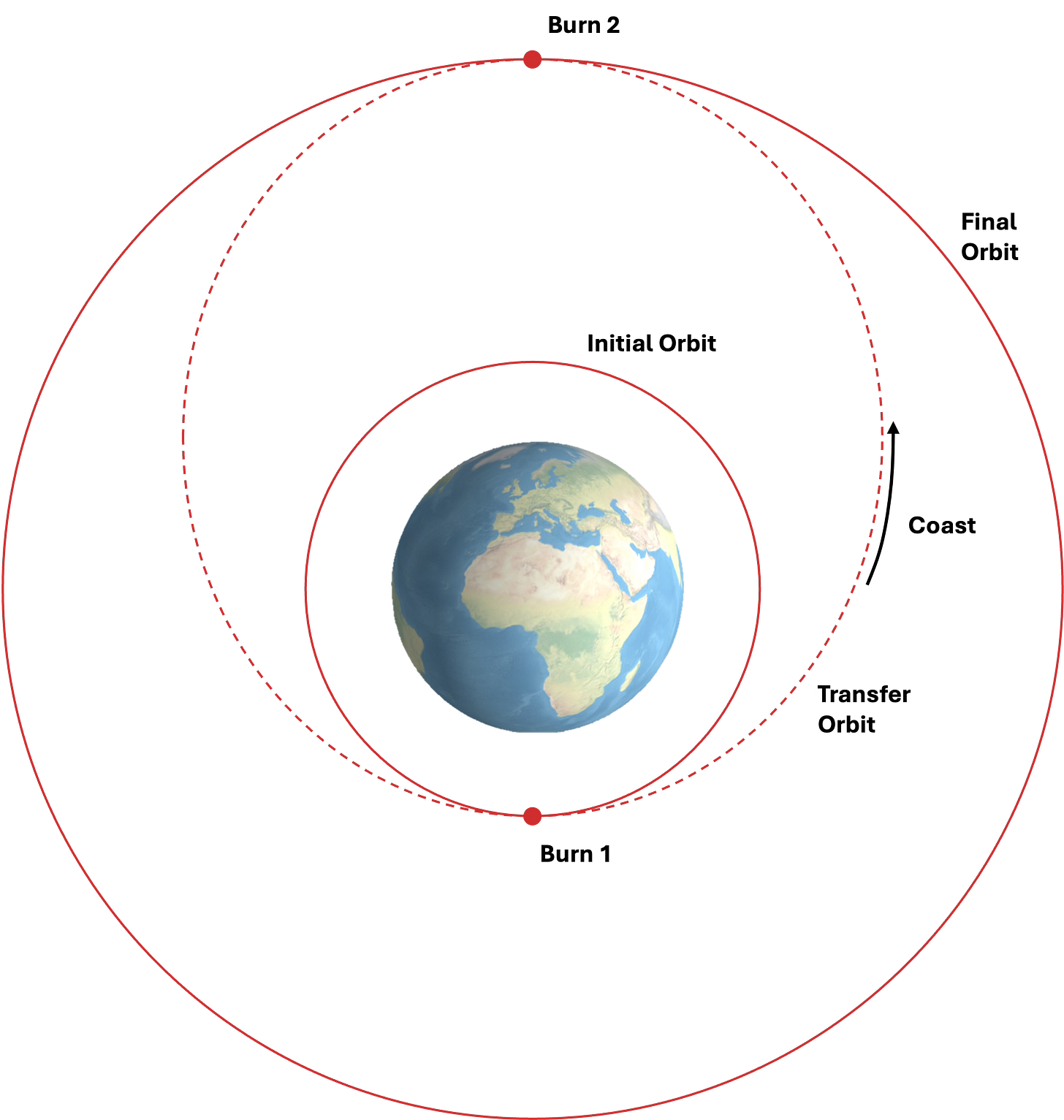

To raise altitude from LEO to higher orbits, we use the highly efficient Hohmann transfer.

This maneuver moves a spacecraft from a circular orbit to an elliptical orbit and then back to a higher circular orbit. Starting in the first, low circular orbit, the spacecraft burns to raise apogee, entering an elliptical transfer orbit. It coasts to the high point — about five hours for LEO to GEO — then burns again to circularize. Moving from LEO to GEO costs about 4 km/s this way.

Plane changes are different. The cost scales with orbital velocity. In LEO, you’re moving fast — 7.8 km/s — so changing inclination is brutal. At GEO altitude, you’re moving under 2 km/s. The same angle change requires a fraction of the velocity. For this reason, plane changes are usually deferred to apogee and combined with circularization burns.

Once you’re in orbit, you’re largely locked in. A LEO satellite can’t just relocate to MEO without burning significant propellant. Space tugs and orbital transfer vehicles exist, but physics still applies.

Choose Your Advantage

The advantage space provides is real, but it isn’t automatic. It emerges from matching the right orbit to the right mission and accepting the trade-offs that follow. Persistence costs proximity. Coverage costs revisit time. Altitude costs delta-v.

The orbit you choose determines the satellite you build, the rocket you need, the ground segment you operate, and the business model you can sustain. Every decision downstream flows from this one.

Orbit isn’t where a satellite lives. It’s what a satellite can do.

Brilliant breakdown of orbital mechanics as mission design constraints rather than just altitude bands. The Molniya orbit example really shows how geopolitical realities drive engineering choices in ways most people overlook. I worked on a telecom project once where we debated MEO vs LEO for months, and this kinda captures why that decision was so painful. The delta-v commitment angle is something that doesnt get enough attention in space infra discussions.

Harry tremendous post here!