How Networks Survive

Babbling idiots, cut wires, and unforeseen failures that threaten a mission

Last week was about sensor redundancy and how to get reliable data into a system. But data is useless if it can’t reach the components that need it. This is where networks come in. They’re the circulatory system of any complex machine, and they face their own failure modes.

A cut wire. A flooded connector. A misbehaving device that spams the network. Any one of these can bring down the system.

The best network architectures make failures irrelevant. Critical functions keep running even when components have failed. This essay explores three strategies to make this happen:

Traffic Separation: Isolating critical and non-critical systems

Redundant Paths: Multiple channels carrying the same data

Self Healing Topologies: Networks that route around failures automatically

Combined, these approaches keep a system functioning through conditions that wouldn’t otherwise seem survivable.

Traffic Separation

The simplest network connects everything to everything else. A single bus carries all messages between all nodes. This works well until one component acts up.

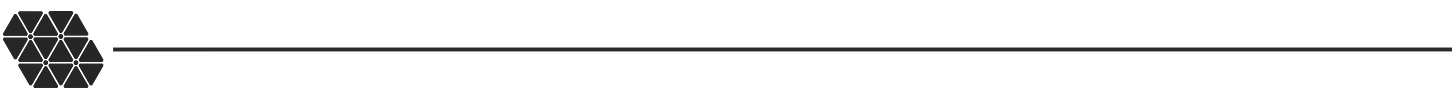

Consider a car’s Controller Area Network (CAN) bus. Bosch introduced CAN in 1986 to simplify automotive wiring, and by the mid 1990s, it was standard equipment on most vehicles. The protocol allows electronic modules to communicate without a central computer. Any node can transmit, and an arbitration scheme establishes message priority.

Modern cars can have upwards of fifty control modules transmitting data.

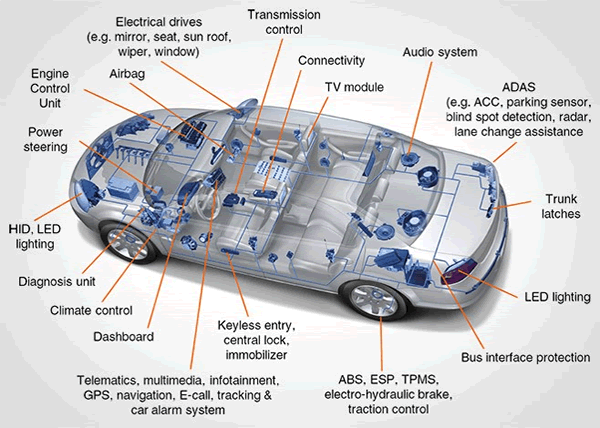

But a single network has a weakness.

A faulty node can monopolize the bus by transmitting continuously, drowning out messages from others. This is known as the babbling idiot failure. One malfunctioning component can silence an entire network.

This can create real risk. If the controller that operates the door locks starts spamming, the brakes might not be able to communicate with the antilock system.

The solution is separation. Don’t put non-critical traffic on the same network as critical traffic.

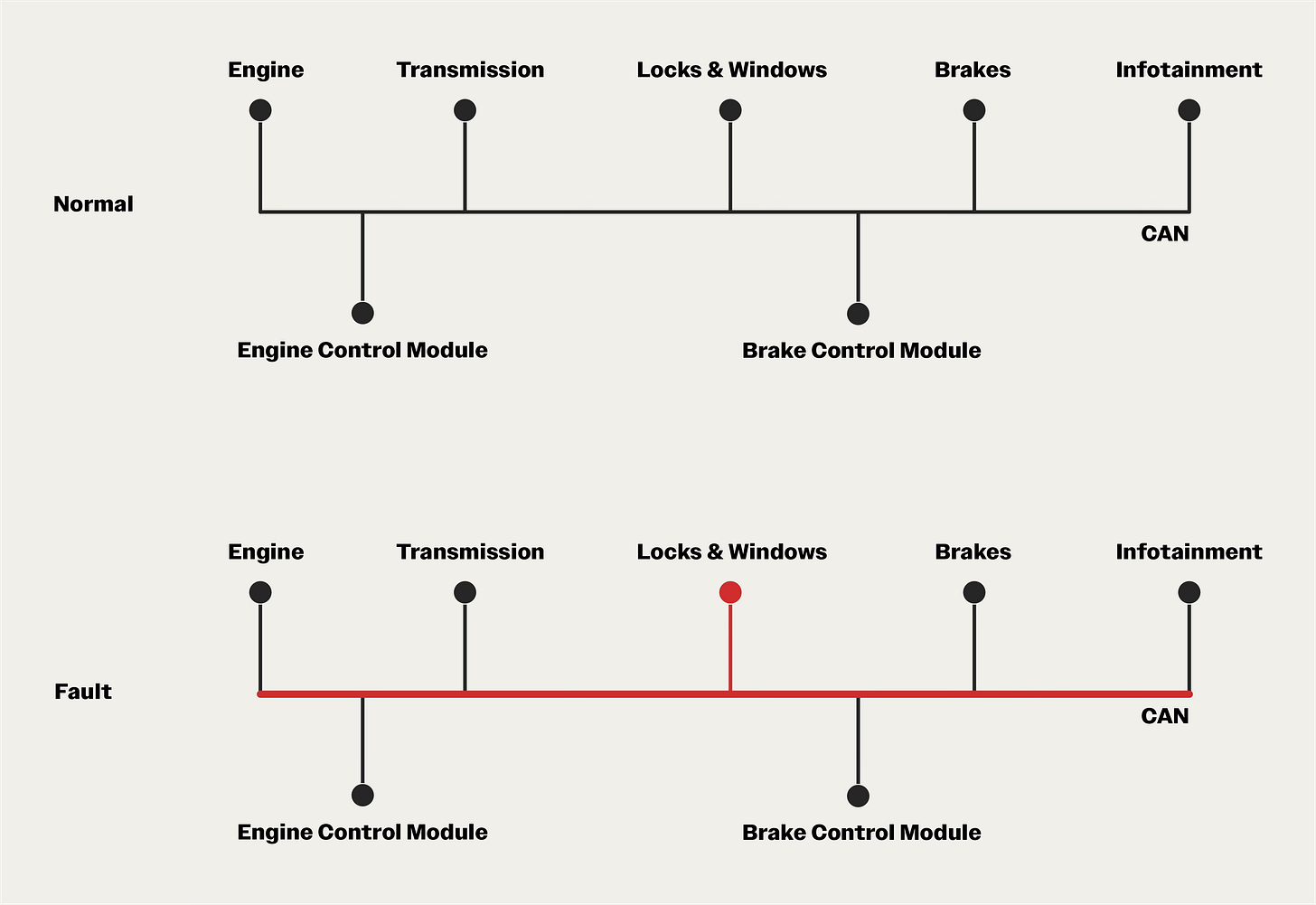

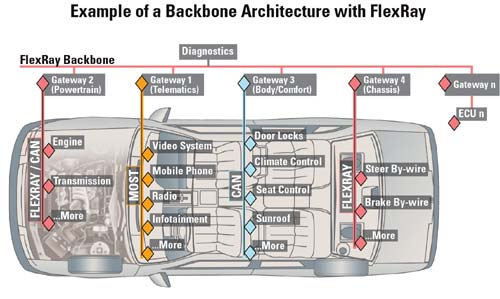

Modern vehicles use multiple networks, each with a different mission:

The powertrain network handles the engine and transmission.

The chassis bus manages steering, brakes, and suspension.

The body/comfort bus coordinates windows, locks, and seat controls.

The infotainment network handles audio, video, and phone connectivity, often using MOST (Media Oriented Systems Transport), a protocol designed for high-bandwidth media.

A central gateway routes messages between buses when needed. But if a Bluetooth module goes haywire on the infotainment bus, the powertrain bus keeps running.

Some cars also include a reserve network. If any one network fails, its traffic can failover to the backup. I’ve often heard this called the party bus, where everyone’s invited when things go wrong.

Even More Separation

Aircraft take a different, more separated approach. Starting in the 1970s, ARINC 429 became the standard. Unlike CAN, it is unidirectional. Each bus has exactly one transmitter that can talk to up to twenty receivers. If you need bidirectional communication, you use two buses.

This architecture is deliberately simple. There’s no arbitration because there’s nothing to arbitrate. Only one device can ever transmit. A babbling idiot can only corrupt its own bus, and since each transmitter has a dedicated bus, a failure affects only the receivers on that specific wire.

ARINC 429’s cost was weight. All those dedicated buses added up to significant wiring. The standard remains onboard older aircraft, but newer designs have shifted to approaches such as AFDX, which combine determinism with network efficiency.

Redundant Channels

Separation protects critical functions from non-critical failures. But what about failures within the critical systems themselves?

For safety-critical applications — brakes, steering, fly-by-wire controls — a single bus isn’t enough. The solution is redundancy: run two or more independent channels carrying the same data.

FlexRay, introduced in 2006, was designed specifically for this purpose. Where CAN offers a single shared bus, FlexRay provides dual channels that can operate independently. The protocol was developed to enable “x-by-wire” systems: brake-by-wire, steer-by-wire, throttle-by-wire.

In a FlexRay brake-by-wire system, brake commands could travel on both Channel A and Channel B simultaneously. If Channel A fails — a cut wire, a shorted connector, a dead transceiver — Channel B continues operating. The brake controller receives identical data on both channels during regular operation and continues on the surviving channel after a failure.

The first production vehicle with FlexRay was the 2006 BMW X5, which used it for an adaptive damping system. Today, FlexRay remains common in premium vehicles for safety-critical applications, even as newer protocols emerge.

FlexRay also includes a bus guardian, which is dedicated hardware that monitors each node and disconnects it if it starts transmitting outside its assigned time slots. A faulty node can’t monopolize the bus because the guardian physically prevents it from transmitting.

Military aircraft have used this dual-channel approach for decades, and spacecraft do the same. These systems often go further with cross-strapping, which configures multiple redundant pathways between nodes so a backup link takes over if the primary fails.

Self-Healing Rings

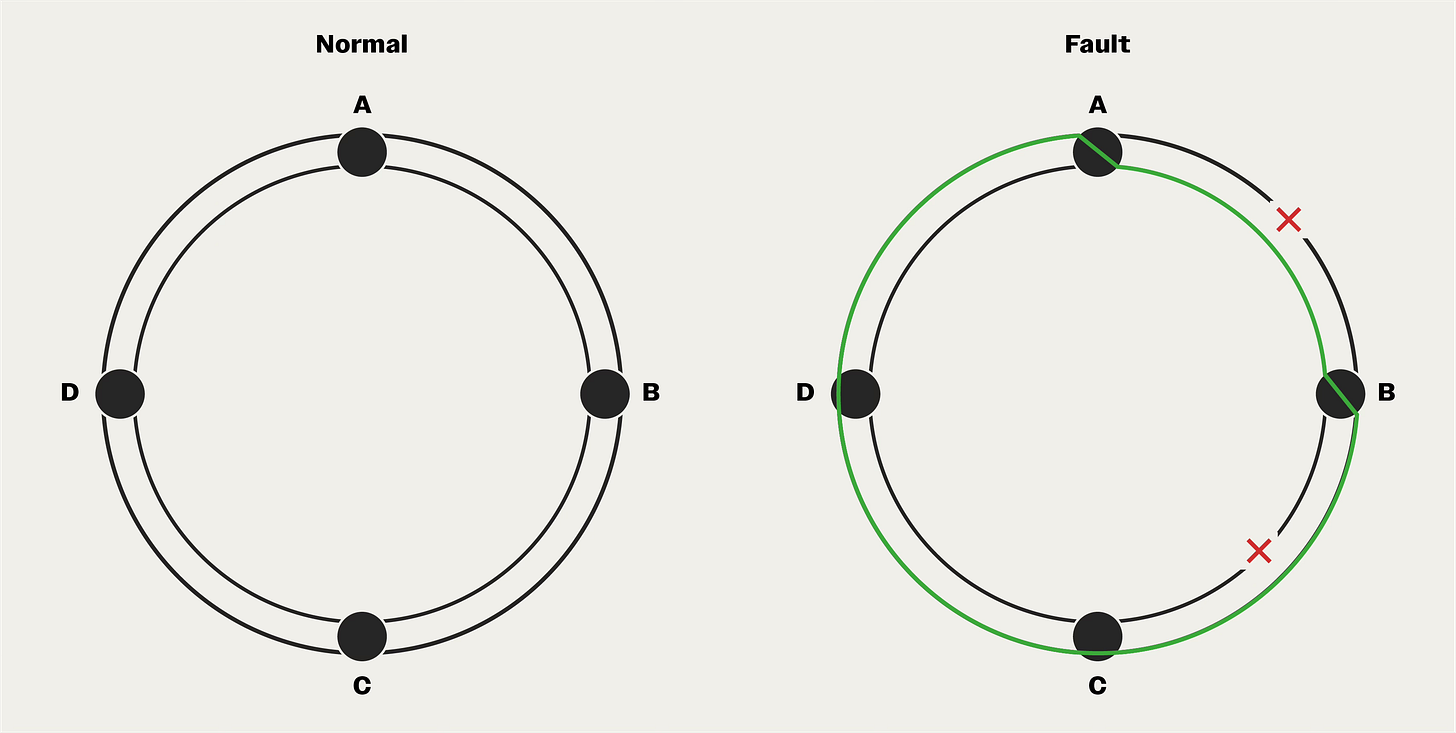

Dual channels protect against link failures. But if a node dies, everything downstream loses connectivity. Ring topologies can elegantly address this problem, creating self-healing networks that can survive a break in the chain.

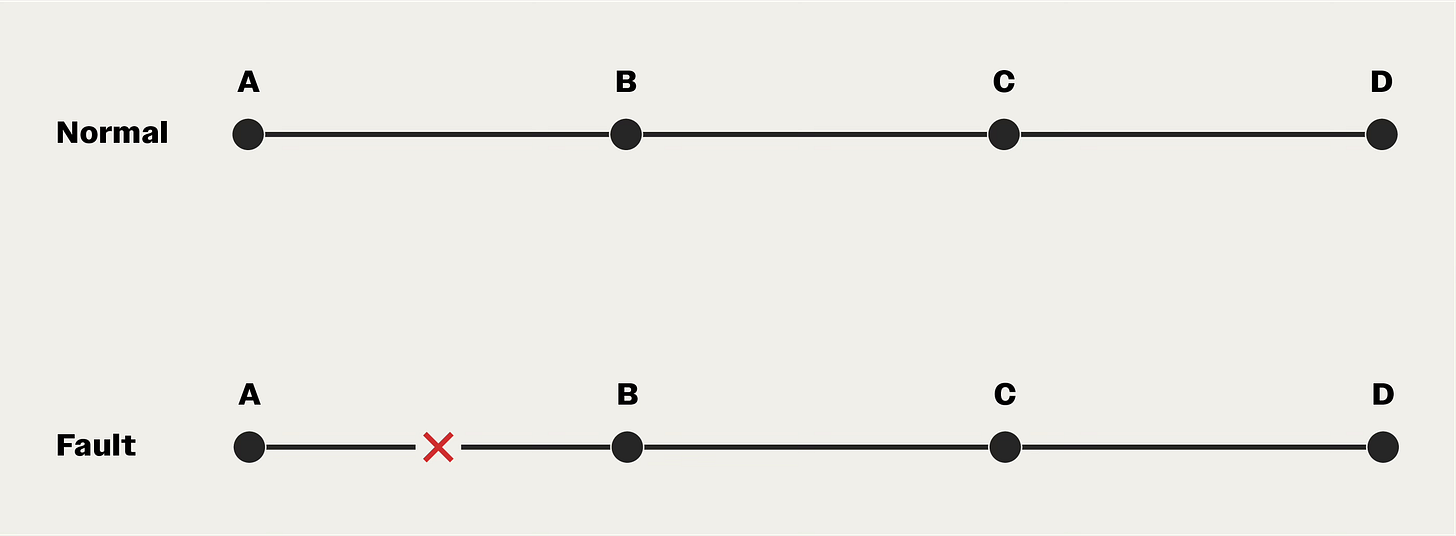

Consider a linear four-node network. A break anywhere could sever communications.

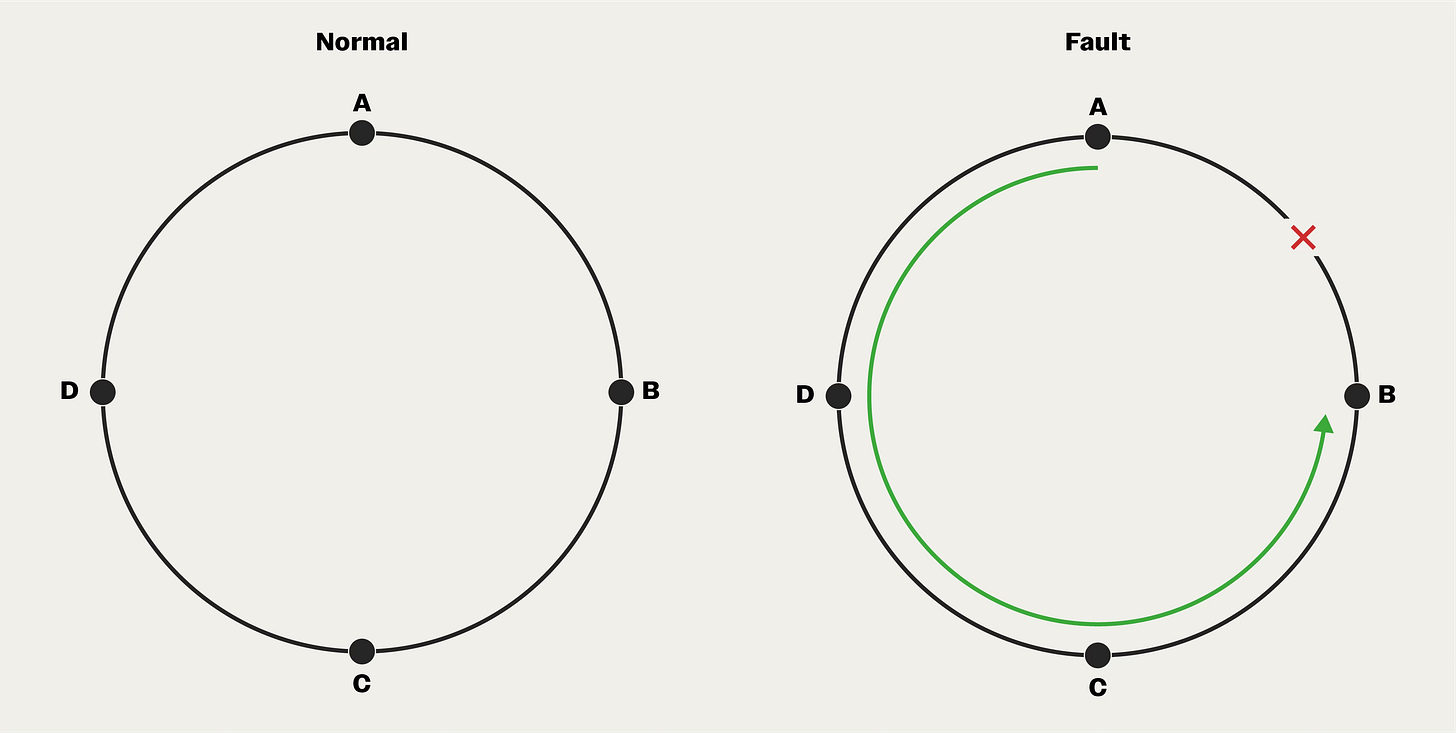

Now, imagine four nodes connected in a circle, with data flowing clockwise. If the wire between Node A and Node B breaks, Node A can no longer reach Node B directly. But it can still reach Node B by going the long way around, through Nodes D and C.

A simple ring provides exactly one alternative path. But what if two wires break?

The solution is the dual counter-rotating ring. Two rings run through the same nodes, but data flows in opposite directions, clockwise on the primary ring, counterclockwise on the secondary.

During normal operation, you can use both rings for bandwidth, or keep one in reserve. When a single break occurs, traffic routes around it on either ring. When two breaks occur in different places, the rings wrap at each break point, forming a single loop that still connects all surviving nodes.

Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI) pioneered the dual counter-rotating ring in the 1980s for local area networks. FDDI itself is largely obsolete, but the architecture lives on in telecommunications backbones, electrical grid networks, and automotive systems.

Tying it All Together

Modern aircraft such as the A380 and 787 have adopted AFDX (Avionics Full-Duplex Switched Ethernet), which combines many of the strategies explored above.

Virtual links: Dedicated logical channels with guaranteed bandwidth and bounded latency, creating the determinism that safety-critical systems demand

Redundancy: Dual networks with sequence numbering so receivers can detect and discard duplicates, similar to FlexRay’s dual-channel approach

Traffic policing: Switches enforce bandwidth limits, acting as bus guardians that prevent any device from flooding the network

The result combines the best of both worlds. AFDX gets the wiring simplicity of a multi-transmitter network, while maintaining fault isolation. Switches contain babbling idiots to their local segment. Redundant networks ensure a single cable failure doesn’t bring down the system. And bounded latency guarantees that brake commands arrive when they need to, every time.

It seems straightforward on paper. But it took decades of careful systems engineering to create such an elegant approach.

Looking Ahead

So far, we’ve explored how systems absorb failures to stay nominal. But sometimes nominal isn’t enough, and a system needs to go beyond its design limits to survive an emergency.

Next, we’ll look at how systems can exceed their 100% operating point to overcome extraordinary conditions, sometimes at the cost of the hardware itself.