How to Fuel a Nuclear Reactor

The geopolitically charged supply chain that powers the world's reactors

Last month, the Department of Energy announced plans to release 19 metric tons of plutonium to the U.S. nuclear industry for reactor fuel. This highlights a crucial reality. Generating nuclear electricity isn’t just about building reactors, it’s also about fueling them.

However, global supply chain for reactor fuel is both complex and thin.

Seventeen countries mine uranium, six convert it to enrichable gas, and nine possess commercial enrichment technology. These activities often take place in different countries. Complicating matters, Russia plays a dominant role throughout.

This raises two questions:

How exactly do we make fuel for reactors?

Does the U.S. have nuclear fuel security?

We’ll explore these questions in a two part essay. This first installment follows uranium’s path from mine to reactor. In doing so, it reveals the degree of U.S. foreign dependence for a variety of fuel services.

This is a big deal today. Nuclear makes up 20% of U.S. electricity generation. But it’ll be an even bigger deal tomorrow, as energy demands surge.

In the second part, we’ll examine U.S. access to nuclear fuel and the tools in our toolkit to assure it. Interestingly, not all of them involve mining more uranium.

The Basics of Reactor Fuel

Nuclear reactors generate energy through fission. A neutron strikes a heavy atom, splitting it into two and releasing enormous energy. The breakup releases additional neutrons that collide with other nuclei, creating a self-sustaining chain reaction.

Uranium is the most common nuclear fuel. In its natural form, it contains two isotopes: uranium-235 and uranium-238. The former can fission, the latter cannot.

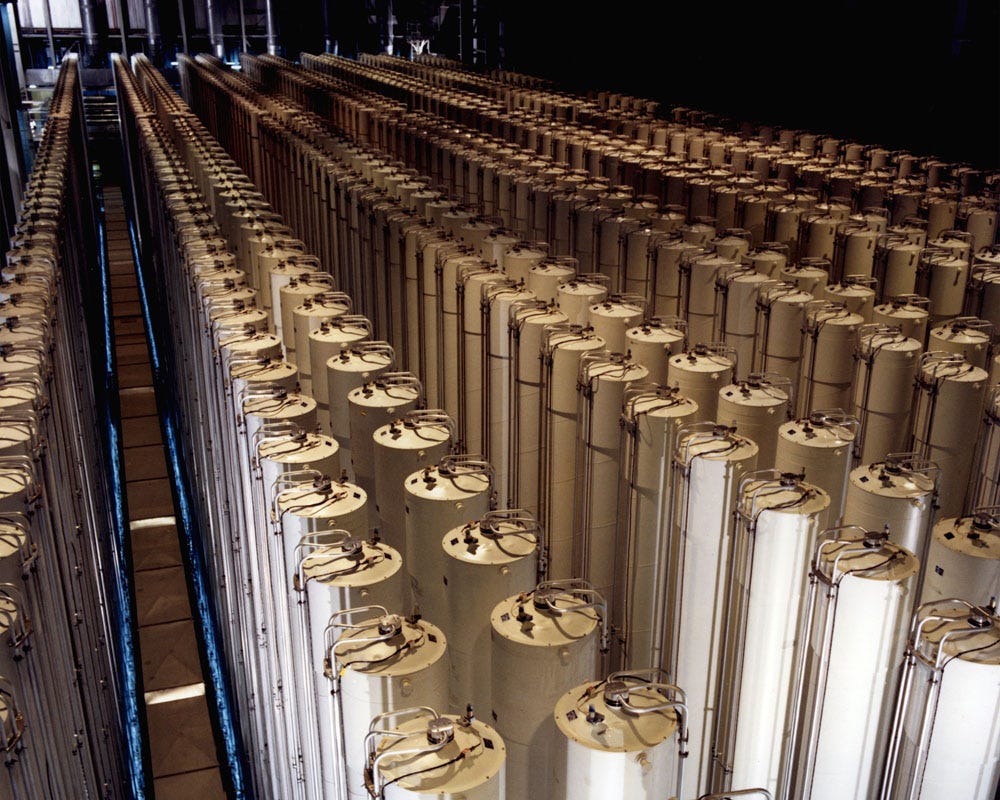

However, the natural U-235 concentration is just 0.7%. In most reactors, this isn’t high enough to sustain a chain reaction. Instead the concentration must be enriched to 3-5% for power plants or above 90% for weapons.

Plutonium can also serve as fuel in many reactors.

Unlike uranium, plutonium doesn’t occur naturally. Instead, it’s produced as a byproduct in fission reactors. When neutrons bombard U-238, it doesn’t fission, but instead absorbs a neutron. This converts it to plutonium-239, which can fission and begins doing so immediately.

Over the course of a standard 18-month fuel cycle, plutonium levels continually increase. By the end, about 30% of the power generated is coming from plutonium that didn’t exist at the start.

In this sense, nuclear reactors achieve what no other power source can. While generating electricity, they also manufacture new fuel.

The Uranium Supply Chain

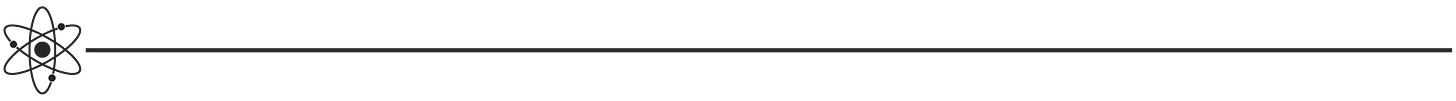

There are five major steps to creating uranium reactor fuel:

Mining and Milling of uranium ore into uranium oxide (U₃O₈), known as yellowcake

Conversion of yellowcake into gaseous uranium hexafluoride (UF₆), known as hex gas

Enrichment of hex gas to increase the concentration of U-235 relative to U-238

Deconversion of hex gas back to solid uranium dioxide (UO₂)

Fuel Fabrication of uranium dioxide into reactor-specific fuel assemblies

Mining, Milling and the Supply Deficit

While uranium deposits exist worldwide, only seventeen countries mine it commercially. Kazakhstan leads with 43% of the global supply, followed by Canada (15%), Namibia (11%), and Australia (9%).

This is where fuel security risk starts.

Except for Canada, every major nuclear power depends on uranium imports. In 2022, the United States required 15,500 metric tons of uranium, 99% of which was imported.

Mining produces solid uranium ore or, in some cases uranium-bearing fluids. Milling then crushes, leaches, and chemically processes this material to produce yellowcake.

There’s also a peculiar supply and demand relationship in the uranium market.

For the last thirty-five years, more uranium has been consumed than produced. In 2022, the global uranium need was 59,000 metric tons. Yet only 49,500 metric tons were produced, covering about 85% of the demand.

Secondary sources fill the production gap. This includes stockpiles from decades of overproduction, reprocessed spent fuel, and downblended weapons-grade material. The strategic implication is that nuclear fuel security doesn’t depend on mining alone.

Uranium currently trades for about $176/kg ($80/pound), which implies the 2022 global annual production of 49,500 metric tons was worth about $8.7B.

Conversion’s Hidden Bottleneck

Conversion transforms yellowcake into hex gas, which the only form suitable for enrichment. Often this step is overlooked for the higher profile mining and enrichment activities that bookend it.

However, conversion is the first global bottleneck and there are only six facilities in five countries with this capability.

The Enrichment Turning Point

Once in gaseous form, uranium can be enriched. This marks the sharp transition from globally traded commodity to tightly guarded asset.

The same equipment that enriches uranium for peaceful power generation can also produce weapons-grade material. For this reason, enrichment facilities are highly restricted, even more so than reactors themselves.

Exemplifying this dynamic, there are numerous global programs that provide countries with reactor fuel in exchange for their commitment to not pursue enrichment technology themselves.

Nine signatories to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) commercially enrich uranium. Notably, Russia makes up 44% of the global capacity. Non-NPT countries such as Iran, North Korea and Pakistan also enrich, but do not do so at a globally commercial scale.

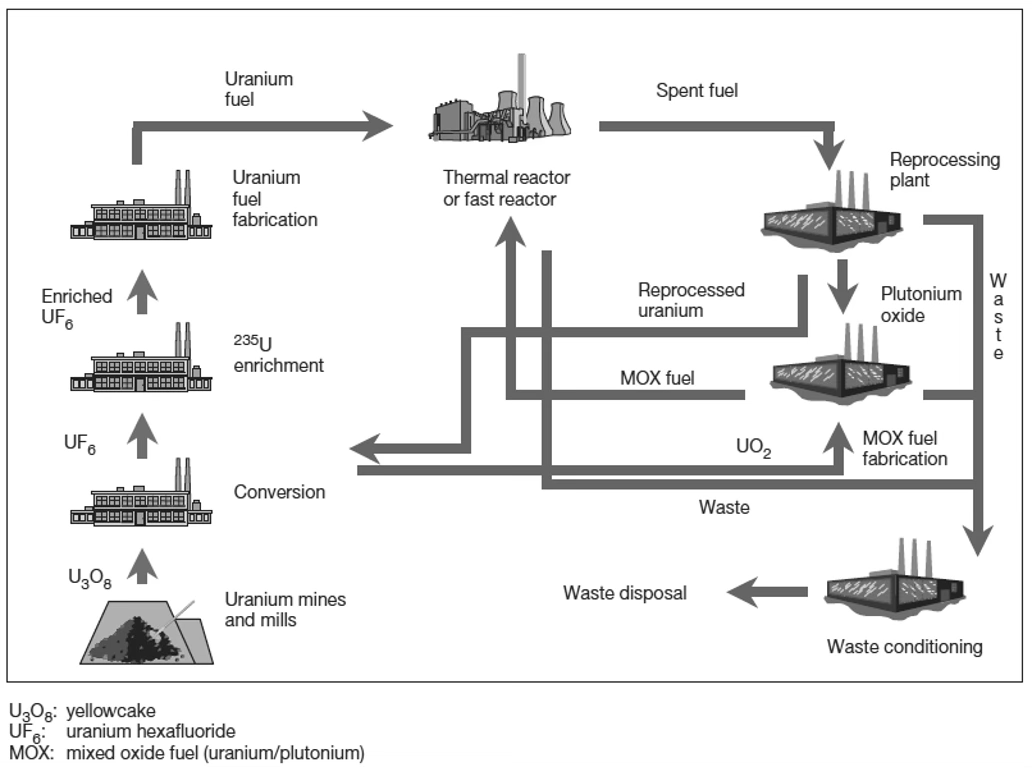

Modern enrichment mostly relies on gas centrifuges spinning in excess of 100,000 RPM. The heavier U-238 molecules migrate outward, while lighter U-235 stays near the center where it’s collected. Thousands of centrifuges are connected in series to create cascades, where each step enriches the product of the last.

About 90% of global enrichment happens this way. Other approaches include electromagnetic and thermal separation, but these are less efficient and generally more dated approaches.

Look to the future, an emerging laser enrichment process has the potential to rewrite the economics of uranium separation. SILEX (Separation of Isotopes by Laser Excitation) uses precisely tuned lasers to selectively excite U-235 hexafluoride molecules, consuming a reported 75% less energy than centrifuges.

With this efficiency gain, SILEX may be able to further enrich depleted uranium — the leftover tails from previous enrichment efforts. Currently, it is not economic to access these stockpiles via centrifuge enrichment.

SWU Economics

Enrichment is measured in Separative Work Units (SWU). This framework quantifies both the technical difficulty of enrichment and serves as the commercial unit for trading enrichment services.

SWU accounts for the complex thermodynamic work needed to separate uranium isotopes. The calculation considers three streams: the uranium feedstock, the enriched product, and the depleted uranium tails. The concentration left in tails—usually 0.2-0.3%—represents an economic optimization between the cost of natural uranium and enrichment services.

The exact global demand for enrichment is difficult to isolate because fuel can be fabricated from secondary sources. However, some estimates place at around 37.6 million SWU per year, which is likely a lower bound.

The price per SWU fluctuates significantly, epecially since Russia invaded Ukraine. The current average market rate is roughly $190 per SWU.

Deconversion and Fabrication

After enrichment, hex gas is converted back into a stable solid. The gas is chemically reduced to uranium dioxide powder, pressed into pellets, and sintered at high temperature. These pellets are loaded into zirconium alloy tubes to form fuel rods, which are welded and inspected.

The rods are then assembled into reactor-specific fuel assemblies—17×17 lattices for most PWRs, 10×10 channel boxes for BWRs, or hexagonal bundles for VVERs. Each design has its own geometry, materials, moderating strategy, and quality controls. Many newer reactors aim to use fuel in pelleted TRISO form for safety considerations.

In some cases fuel fabrication is performed by the reactor vendor and in others by independent fuel companies. Some nations import entire assemblies, while others maintain their own fabrication lines as part of their energy security strategy.

Plutonium and MOX Fuel

We discussed earlier how plutonium created in-situ can power reactors. But it can also be loaded directly into a reactor at the start of the fuel cycle.

Reactors can be loaded with Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX), which is a blend of 3-12% plutonium oxide and depleted uranium. MOX has powered forty four reactors globally, with France operating twenty two that combined generate 10% of French electricity.

In general, fast reactors can use MOX far more efficiently. These units use unmoderated fast neutrons that convert U-238 into plutonium while burning existing plutonium. Some designs achieve breeding ratios above 1.0, producing more fissile material than they consume.

Generating Power from Weapons

An alternate source of reactor fuel comes in the form of former weapons.

Weapons-grade uranium is highly enriched to 90%+. It can be combined with depleted uranium (<0.3%) to create reactor fuel at 3%-5%.

The Megatons to Megawatts Program demonstrated this at scale. From 1993 to 2013, Russia downblended 500 metric tons of weapons-grade uranium into reactor fuel—roughly equivalent to 20,000 Soviet warheads. This was sold to the U.S. and generated approximately 10% of U.S. electricity over the period.

In another example, known a Project Sapphire, the U.S. airlifted 600 kilograms of highly enriched uranium from Kazakhstan in 1994. The weapons grade material has been found barely guarded in a former Soviet facility. The U.S. procured and secured the material, transporting it to Tennessee to become reactor fuel.

The U.S. has also downblended part of its own nuclear arsenal. Beginning in the late 1990s, the Department of Energy converted roughly 160 metric tons of highly enriched uranium—drawn from retired warheads, naval fuel, and other military stocks—into low-enriched uranium suitable for civilian reactors.

Plutonium from dismantled nuclear weapons can also be turned into reactor fuel. Weapons often contain metallic plutonium, which is chemically converted into plutonium oxide and blended with depleted uranium to form MOX.

Russian Involvement

Russia holds a large position in the global reactor fuel market. The country has broad capabilities, and the world became accustomed to procuring fuel from Russia through Megawatts to Megatons and other programs.

As a point of reference, Russia historically accounted for 25% - 30% of uranium imports into the U.S.

The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 complicated this. Yet, while the world wanted to decouple from Russian uranium, it was easier said than done.

The U.S. quickly issued broad sanctions against Russia, but uranium was exempt from them. Later in August 2024, new legislation prohibited uranium imports from Russia, but allowed for waivers through 2028. Russia retaliated with a ban on uranium exports to the U.S.

Towards the end of 2024, Russia-U.S. uranium trade had nearly halted. However, it resumed on a case-by-case basis in early 2025. In February, the vessel Atlantic Navigator II delivered 100 tons of enriched uranium to the port of Baltimore.

Given bilateral restrictions, future imports are uncertain. However, one U.S. company, Centrus, has announced they’ve secured waivers for Russian imports through 2027.

Where does this leave us?

Annually, the U.S. requires approximately:

15,500 metric tons of uranium of which 99% is imported.

12 million SWU of enrichment of which 60% is imported.

In other words, we have a high dependence on foreign sources for commercial nuclear fuel.

As the U.S. refocuses on nuclear reactor development the needs will only increase. As a result, there is heightened focus on assuring access to nuclear fuel for the U.S.

In May 2025, the DOE moved to reshape its surplus plutonium strategy. An executive order directed the DOE to stop its longstanding disposal program and instead establish pathways to make surplus plutonium available as advanced reactor fuel.

Under the resulting initiative, about 19 metric tons of plutonium are being offered to U.S. reactor developers, particularly those working on fast reactors. The effort is significant, but remains at the pilot stage rather than full commercial scale.

This brings us to the core question: Does America have nuclear fuel security? And if not, what tools exist to achieve it?

Part 2 examines seven such tools. These range from mining more uranium domestically and bolstering enrichment capacity to re-enriching depleted uranium, downblending weapons and activating advanced reactors.

Pathways exist, and we’ll consider the political will and capital backing required to pursue them.

General References

OECD Nuclear Energy Agency. Uranium 2024: Resources, Production and Demand. Paris: OECD Publishing, April 2025. https://www.oecd-nea.org/upload/docs/application/pdf/2025-04/7683_uranium_2024_-_resources_production_and_demand_2025-04-22_14-29-2_928.pdf.

Bellona Foundation. “How Will the US Ban Russian Enriched Uranium Impact Both Countries?” Bellona.org, May 2024. https://bellona.org/news/nuclear-issues/2024-05-how-will-the-us-ban-russian-enriched-uranium-impact-both-countries.

Financial Times Markets Data. “Company Announcement.” PR Newswire, November 5, 2025. https://markets.ft.com/data/announce/detail?dockey=600-202511051704PR_NEWS_USPRX____PH16561-1.

International Panel on Fissile Materials. “United States.” Fissile Materials. Accessed November 12, 2025. https://fissilematerials.org/countries/united_states.html.

OECD Nuclear Energy Agency. “Uranium: Resources, Production and Demand (Red Book).” OECD-NEA. Accessed November 12, 2025. https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_28569/uranium-resources-production-and-demand-red-book.

World Nuclear Association. “Conversion and Deconversion.” Information Library: Nuclear Fuel Cycle. Accessed November 12, 2025. https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/conversion-enrichment-and-fabrication/conversion-and-deconversion.

William Blair & Company. “SWUning Over Nuclear Deregulation and Expanding Enrichment Capacity.” William Blair Insights. Accessed November 12, 2025. https://www.williamblair.com/Insights/SWUning-Over-Nuclear-Deregulation-and-Expanding-Enrichment-Capacity.

International Atomic Energy Agency. Country Nuclear Fuel Cycle Profiles. Technical Reports Series No. 425. Vienna: IAEA, 2005. https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TRS425_web.pdf.