The Shape of Industrialization

How what’s owned and what’s outsourced defines an organization

Welcome to As Built! This concept of a company’s “shape” has evolved in my mind over the last few years. I started my career at SpaceX, which programmed me to vertically integrate everything. In the time since, it’s become clear that’s just one shape, and many others can be successful too. This analysis is all very high level and thematic, but I find it helpful to contextualize the positioning of various companies. I hope you do too!

The U.S. is reindustrializing. This brings visions of factories and steel mills, hot sparks flying, and durable goods rolling off production lines. But manufacturing is just one — albeit very important — dimension of industrial capability. Instead, industrialization requires three fundamental capabilities: the ability to design complex systems, manufacture them at scale, and operate them effectively.

Each of these three categories has many tiers. In manufacturing, we naturally think of the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) and their Tier 1-4 suppliers. Design has the same depth. A company might perform overall system design while outsourcing subsystem and component work to specialist firms.

Operations spawns its own ecosystem. The final user might be the manufacturer itself, or an entirely separate company using the hardware to deliver services. Additionally, someone must maintain these systems, whether it be the operator, manufacturer, or third-party specialists.

The pattern of who owns what across these three phases—what we’ll call the “shape” of industrialization—determines everything from development speed to capital requirements to competitive resilience. Mapping the shapes can illuminate where a company fits, what role it can play, and what challenges it will face as it scales.

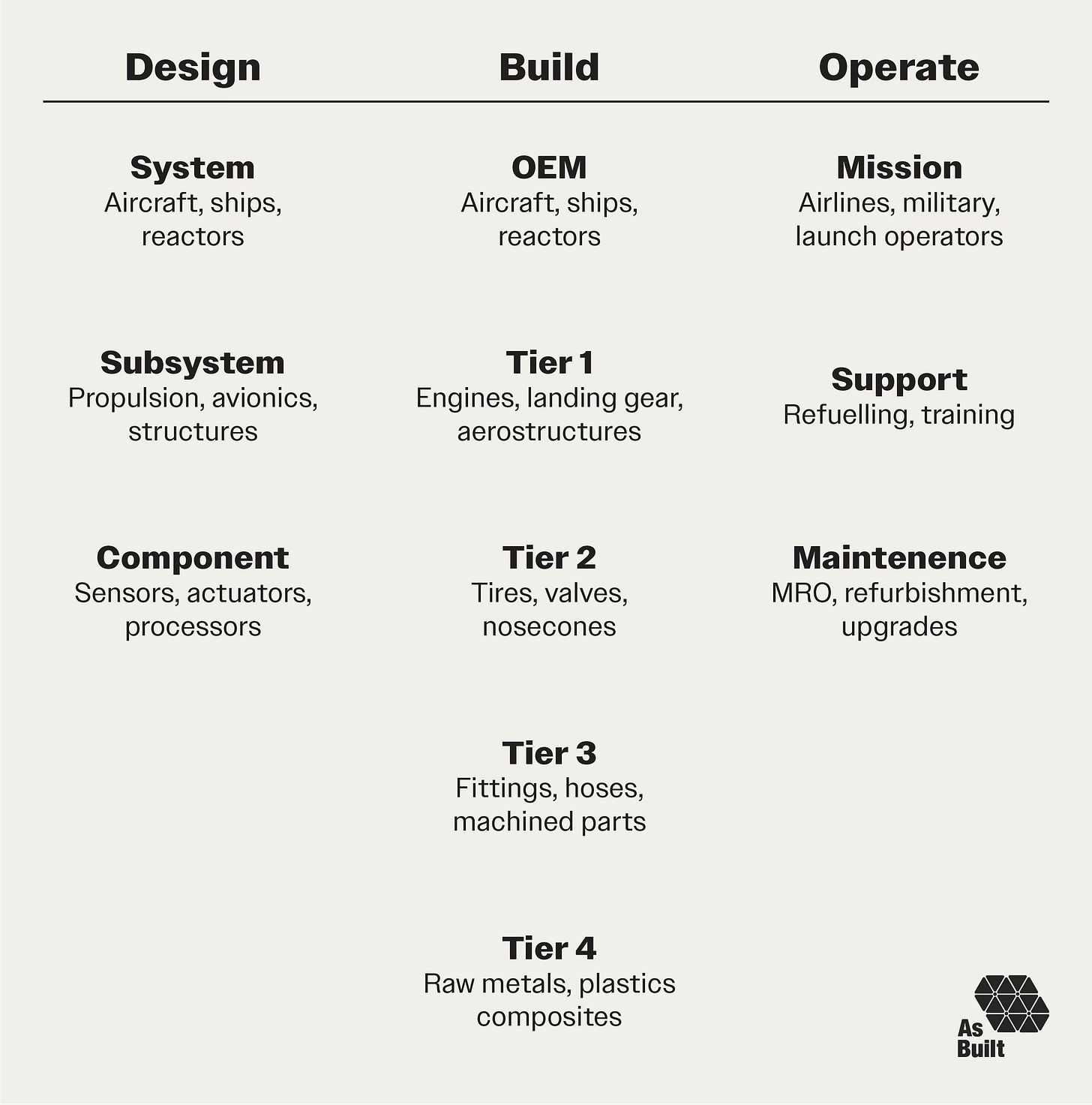

Making a Map

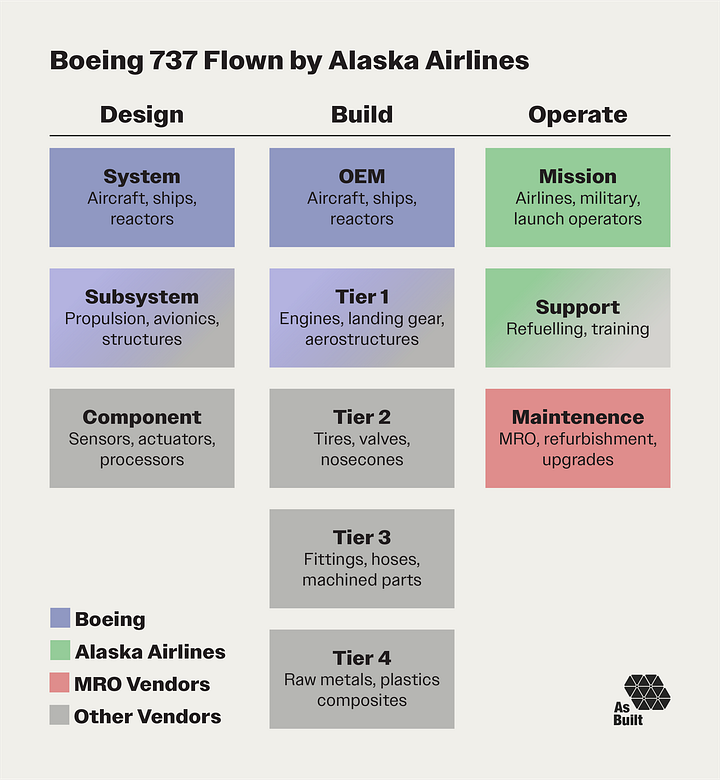

We can arrange the three phases — design, manufacturing, and operations — on a map, along with their respective subgroups. In doing so, we start to see how the industrialized ecosystem works, noting that the mission activity under operations (top right) is ultimately where end-user value is delivered.

Besides these three phases, testing and logistics also play critical supporting roles. Every part that’s built must be validated through via test, which can have significant infrastructure requirements and other costs. Likewise, transporting and warehousing the hardware can drive substantial operations. While these activities are critical, for this discussion, we’ll consider them as elements within the three main phases above.

The Shapes of Industry

This map becomes powerful when we use it to visualize real organizations. The cells each company occupies — and avoids — tell a story about strategy, capability, and competitive positioning. We’ll consider five examples to illustrate how different programs position themselves through different shapes.

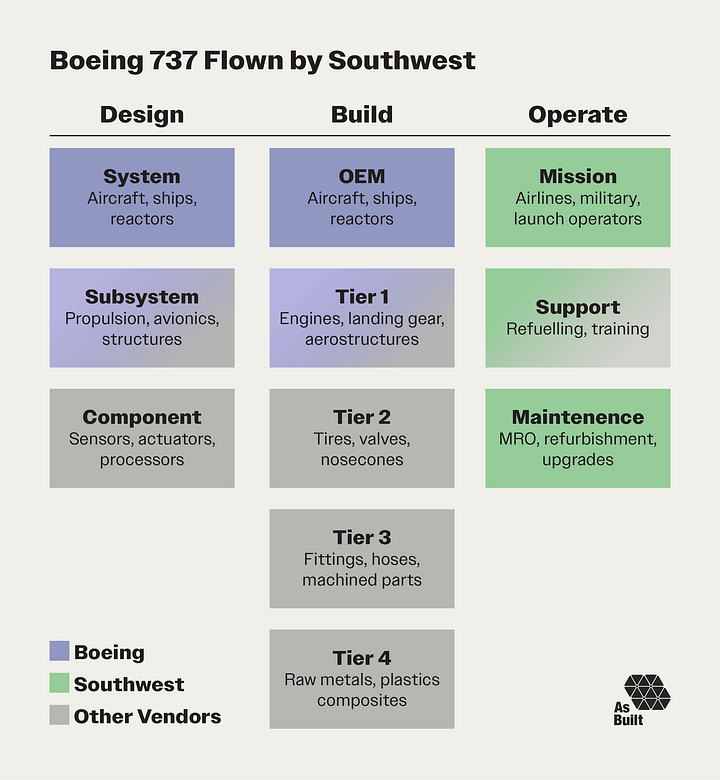

Boeing 737 Aircraft

Consider the Boeing 737. Its mission is to deliver transportation services to traveling customers.

Boeing designs the top-level aircraft. They do some subsystem design (structures) but outsource much of it. For example, the engines come from CFM International, which is a joint venture between GE and Safran. At the component level, most design is outsourced to vendors that make commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) parts, such as pressure sensors or connectors.

When it comes time to manufacture the plane, Boeing does the final aircraft integration as the OEM. Tier 1 systems are mostly outsourced. Engines come from CFM. Spirit AeroSystems makes the fuselage. Down at Tier 2, Collins Aerospace provides components and mechanisms. In total, the 737 reportedly has 600 suppliers across the Tier 1 & 2 levels, and even more are expected at the lower levels. Tier 4 materials are mostly outsourced, with companies such as Hexcel and Toray Industries supplying composites and other materials for the structural assemblies.

This arrangement positions Boeing on top of the design and manufacturing phases, performing the most integrated work, while outsourcing much of the rest.

The operations phase reveals a key distinction. Boeing is no longer at the top. Instead, airlines such as Southwest and Alaska Airlines provide mission services by flying customers around the world.

Some support activities are outsourced. Refueling services are procured from airports. Food and beverages restocking often comes from vendors. Pilot training is a mix. Boeing runs a training division that some airlines rely on. Conversely, Southwest operates its own flight training center.

When it comes to maintenance, refurbishment, and overhaul (MRO), the industry also diverges. Southwest operates its own MRO facilities and performs heavy maintenance on its 737 fleet, which is one of the largest in the world. At the other end of the spectrum, Alaska Airlines performs light repairs but outsources heavy MRO activities to companies such as AAR Corporation.

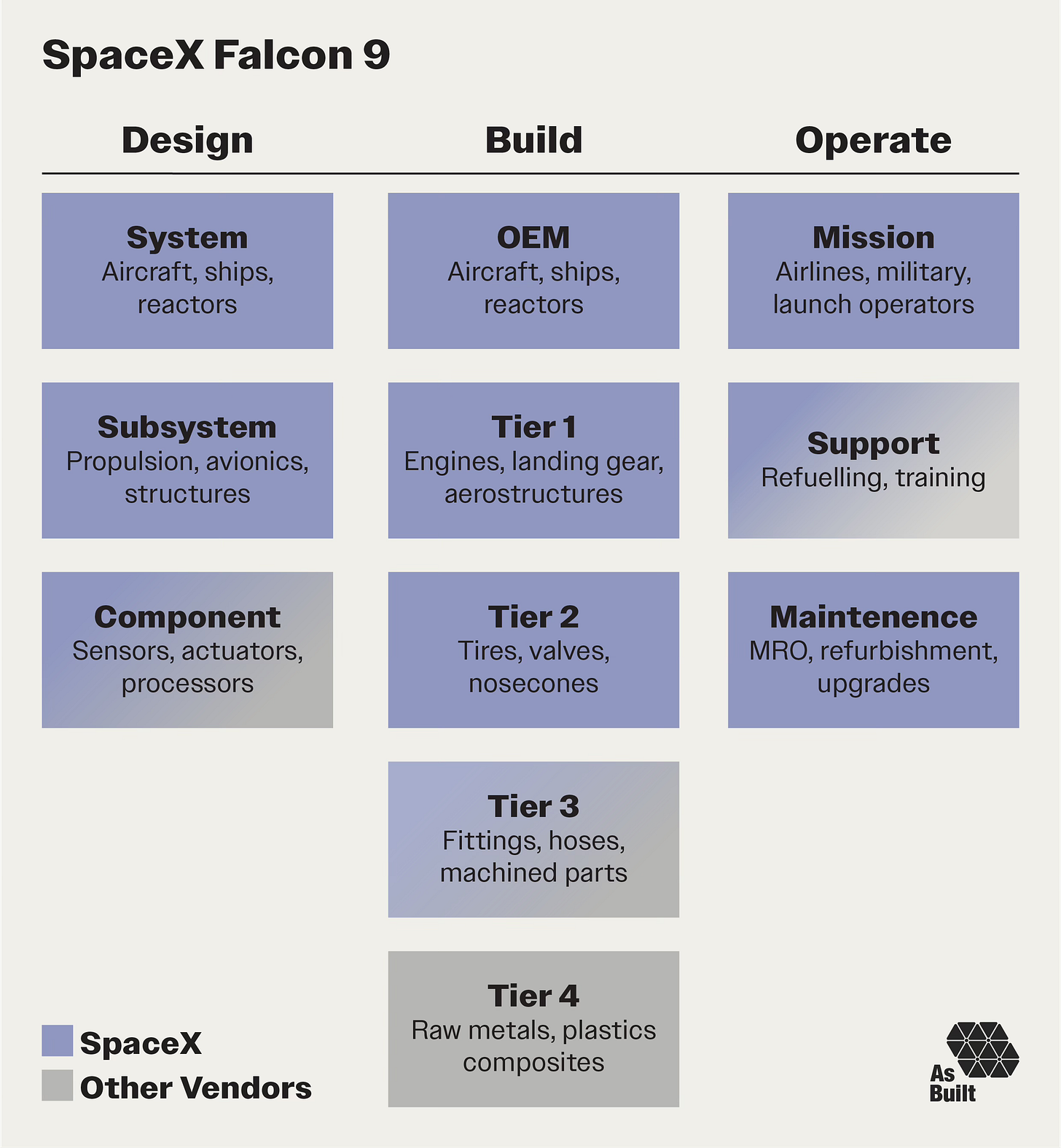

SpaceX Falcon 9 Launch Vehicle

The shape of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 program is dramatically different. SpaceX is both highly verticalized from a design and manufacturing standpoint, and they are the end service provider. In Boeing’s case, it builds the 737 and sells it to airlines to operate. In SpaceX’s case, they build Falcon 9 and operate it themselves, transporting customer satellites to space.

In the design phase, SpaceX performs most engineering work in-house. This starts with the vehicle-level design for Falcon 9. It extends to the subsystem design of the Merlin engines, the avionics suite, and the primary structure (equivalent to an airplane’s fuselage). At the component level, SpaceX also performs significant design of mechanisms, valves, and sensors, though some of these are procured as COTS.

The manufacturing phase mimics the verticalization of design. For most hardware, SpaceX serves as the OEM and the Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers. At Tier 3, it’s a mix. Machined parts are split between in-house and outsourced. Some COTS items are procured. At Tier 4, SpaceX generally procures raw materials but has also done some in-house metallurgical work.

In the operations phase, SpaceX again is verticalized. They launch the rocket, and for several years, I was fortunate to be an operator in mission control for Falcon 9 launches. They also manage their own launch sites and handle refueling and other support activities. Finally, SpaceX performs all refurbishment for boosters that have landed before they’re relaunched.

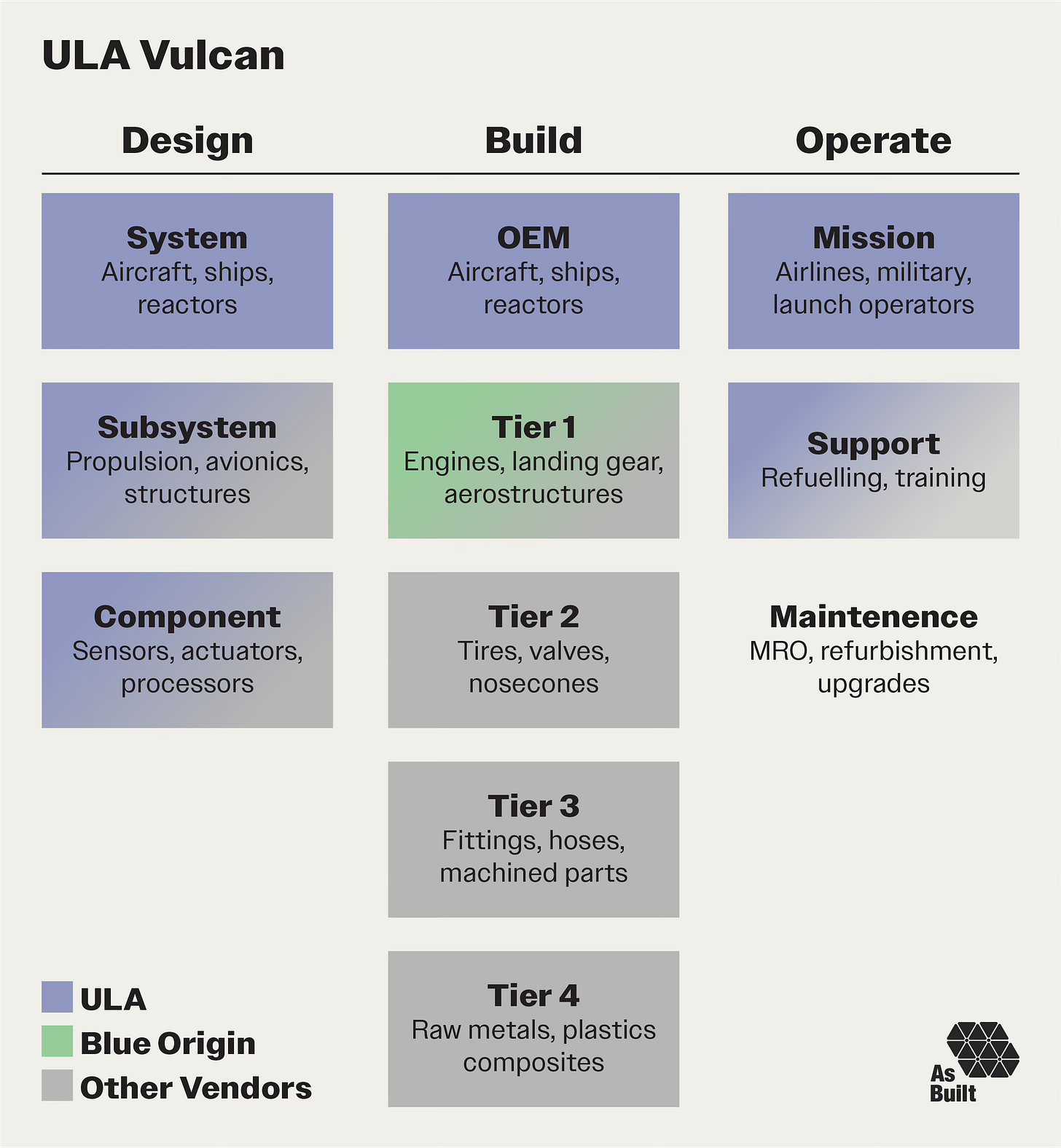

United Launch Alliance Vulcan Launch Vehicle

United Launch Alliance (ULA) provides a good contrast to Falcon 9. ULA operates the Vulcan launch vehicle and performs the top-level design, build, and launch operations.

However, they tend to procure more Tier 1-3 components from vendors. In particular, ULA buys engines from Blue Origin to power Vulcan. As a result, their shape takes on a different form in the mid tiers of design and manufacturing.

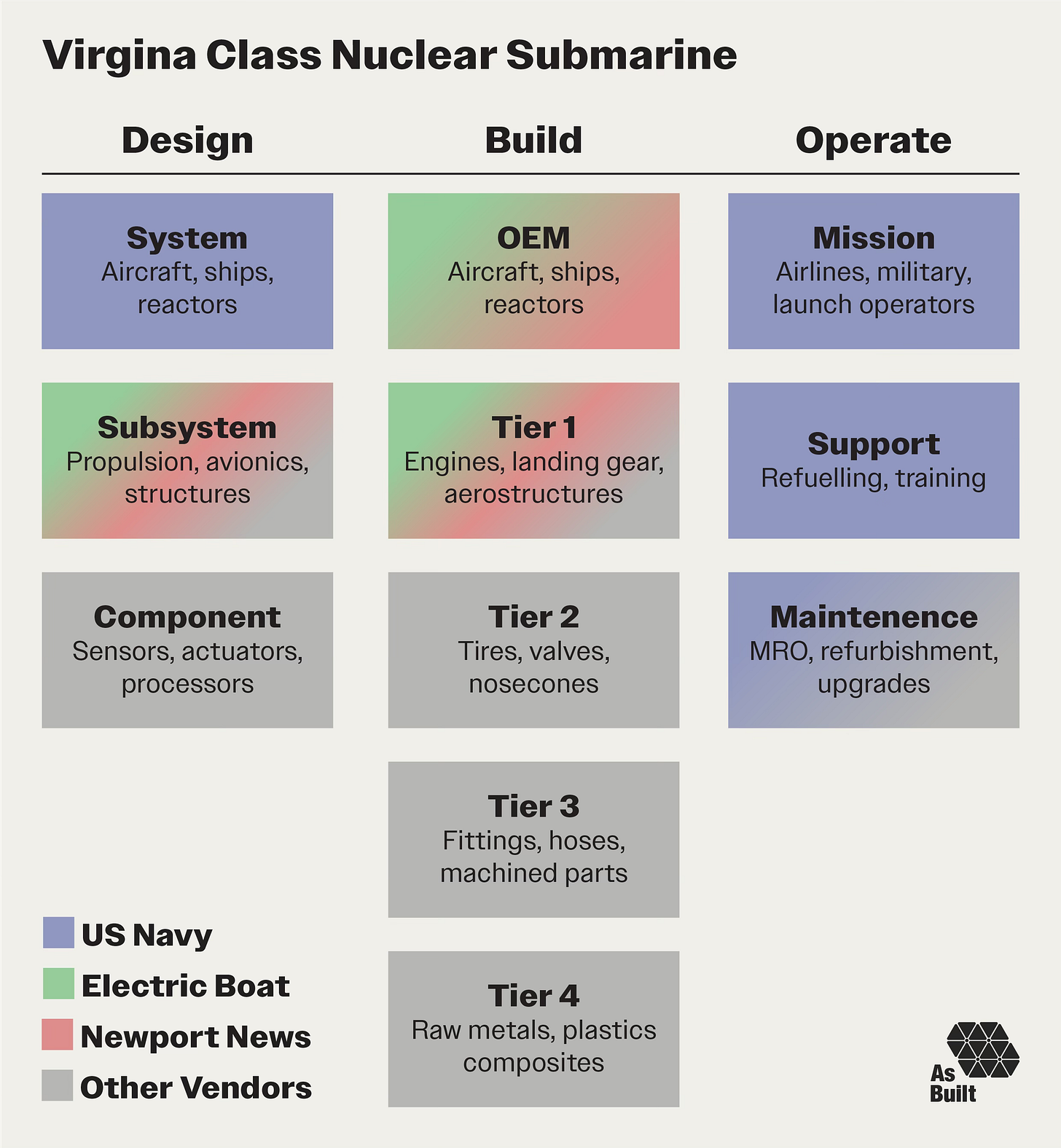

U.S. Navy Virginia-class Submarine

The Virginia-class submarine program creates yet another distinct shape: distributed industrial capability integrated by government oversight, with exclusive military operations.

In the design phase, the submarine program splits responsibilities. General Dynamics Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries Newport News Shipbuilding share the system-level design under Navy oversight. Major subsystems are designed by specialists — nuclear reactors by BWX Technologies, combat systems by Lockheed Martin, and sonar by Northrop Grumman.

Ultimately, the Navy maintains final design authority, even if through contractors. For this reason, here we’ll categorize them as the system design owner.

Manufacturing follows a similar distributed pattern. Electric Boat builds the bow, engine rooms, and command and control systems, while Newport News builds the stern, habitability, and machinery spaces. The yards alternate responsibility for the final assembly of each submarine.

Tier 1 suppliers span many of the traditional defense contractors, such as Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, as well as specialists like BWX Technologies for the reactor components and Kollmorgen for the mast. This industrial base represents thousands of suppliers across all tiers, carefully managed to maintain the strategic capability.

The operations phase is where the shape becomes unique. Unlike commercial models, the Navy operates these submarines exclusively. The Navy trains all crews and conducts all missions. Contractors support maintenance and modernization, but under Navy supervision. This shape exists to ensure production of a key national security system, that has little commercial overlap.

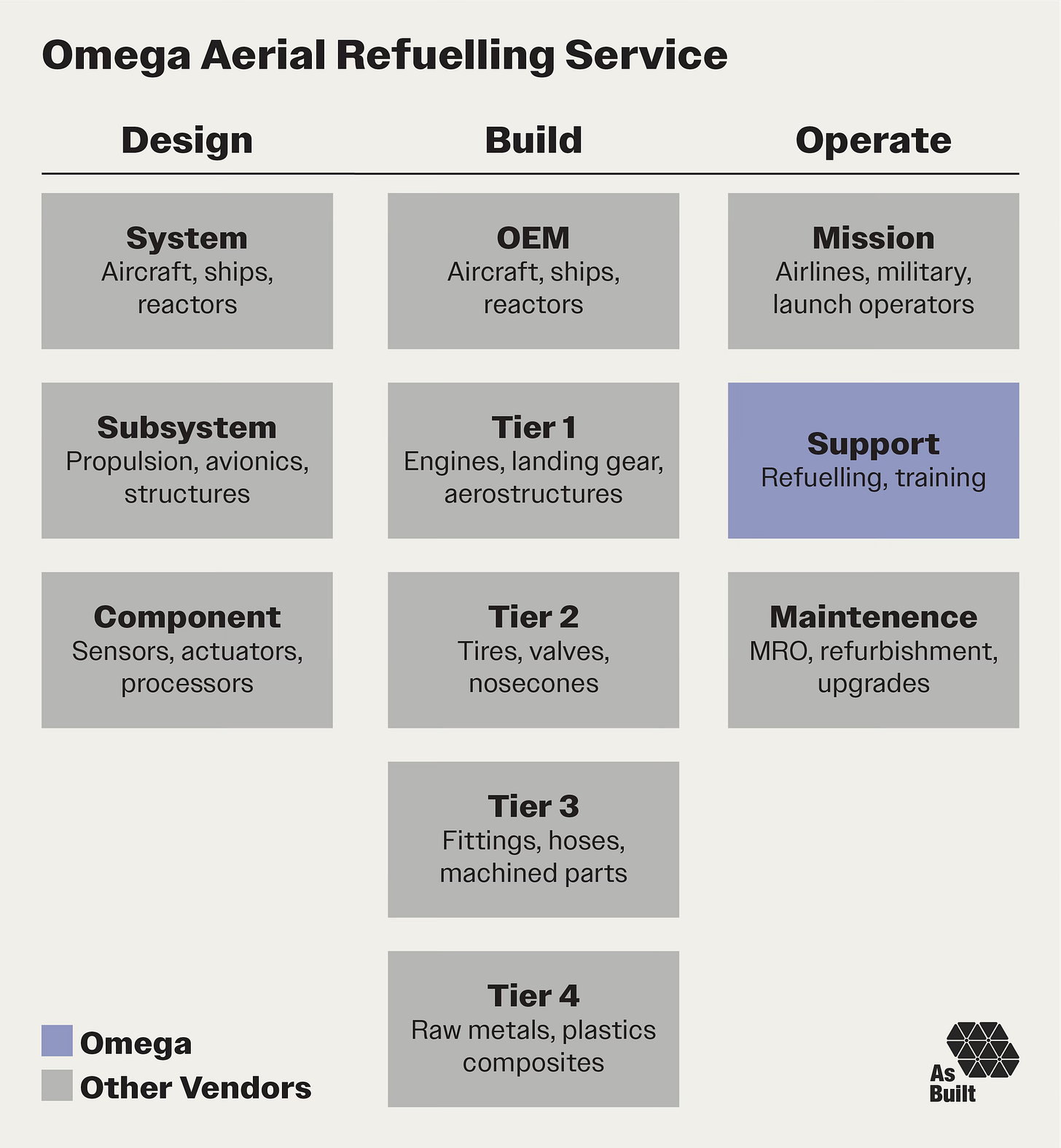

Omega Aerial Refueling Services

Omega Aerial Refueling Services is a unique, lesser known case study. During combat operations, the military provides aerial refueling. However, Omega has carved out a niche in providing aerial refueling for training, exercises, flight testing, and long cross-country or overwater movements.

The firm operates a fleet of six KC-707 and KDC-10 aircraft that can provide contract aerial refueling to military aviation. When we look at Omega’s industrialization map, they occupy just the mission support cell under the operations phase.

Note that shapes shift with perspective. We could map this differently, showing the Navy operating fighters that Lockheed Martin designs and builds. But viewing Omega alone best illustrates this specialized model.

Likewise, we could even draw an organization’s domain-specific shape — its map for propulsion or avionics. Often these shapes diverge for the same company.

How Shape Determines Performance

Why do these shapes matter? The form they take influences how the organization operates across a variety of dimensions. Six of the most important are considered below.

Control, Responsiveness, and Insulation

A bigger shape means greater control. For example, a team can design the exact system they need without compromising for vendor availability.

It also enhances responsiveness. During development, there will be learnings. A part might break or not fit as expected. Verticalized groups can respond rapidly. Designs can be quickly modified, and new parts machined.

During heavy engine development at ABL, this was a big enabler for the program. We could run an engine test, identify the need for a new turbopump impeller, design and machine that new impeller, and get the engine back on the stand all within two days. If this were outsourced, it would take weeks, if not months.

Verticalized businesses also often have a degree of insulation that protects them from things like short-term shocks. If there aren’t many vendors in the supply chain, then global disruptions won’t have a big impact.

Speed

Many often cite verticalization as a speed enabler. While true in some scenarios, it can be detrimental in others.

As illustrated above, vertical integration can mean more control and responsiveness, accelerating the program. The designers of the Sten gun carefully prescribed every feature of every component in the weapon. This extreme degree of design for manufacturing led to legendary build times.

However, verticalization also means that there’s more that must be done. If we want to machine parts in-house, we need to build a machine shop, hire a team, and get it running smoothly, all before we can machine your first part. If we outsource, parts arrive in weeks. Both paths have their benefits, and speed must be considered case by case.

Intellectual Property and Competitive Moats

Vertical integration can create stronger intellectual property protection and deeper competitive moats. When organizations build in-house, innovations remain proprietary, and competitors cannot access the same capabilities simply by working with shared suppliers.

This dynamic explains why traditional aerospace companies often compete on system integration rather than component innovation.

Capital Requirements

Capital requirements generally increase with the size of the shape. Every activity performed requires facilities and infrastructure, so highly verticalized businesses face large upfront capital requirements. They also maintain larger teams, driving operational expenses.

For example, cutting new turbopump impellers meant we had to build and staff an entire machine shop, operating nearly around the clock.

However, in the longer term, vertically integrated entities should achieve better margins, resulting in lower long-term capital needs.

Financial Opportunity

Larger shapes typically create higher financial opportunity. If this weren’t true, expansion wouldn’t make sense.

Increased financial opportunities come in several forms. Performing more activities enables the company to capture what would otherwise be its vendors’ profit margins. Additionally, operational efficiencies often reduce costs across the operations. Finally, a larger shape may create new revenue streams. Some verticalized capabilities can themselves become business units.

Risk

Industrial efforts face a variety of different types of risks, and a company’s shape determines its risk exposure. There’s engineering risk: does the design work? Build risk: can we make parts to the required quality? Team risk: can we hire and develop the right people? Capital risk: can we finance it all? The more a program does in-house, the more risks fall into its portfolio.

When we outsource, these risks don’t disappear—they transfer to our vendors. These risks consolidate to become supply chain risk from our perspective. Vendor delivery becomes the critical uncertainty.

In many cases, a smaller shape reduces risk exposure. Airlines carry fuel cost risk. When aviation fuel prices spike, their margins suffer. Boeing avoids this immediate exposure, though sustained high fuel costs eventually impact aircraft sales.

What Shape is Right?

There’s no universal answer. The optimal shape depends entirely on an organization’s specific context and constraints. If there’s time and resources to run an in-house spiral development program, that could make sense. If not, it might be best to start by buying COTS hardware.

Most founders coming out of SpaceX highly verticalize their startups. This has clear and proven advantages, but strictly pattern-matching can be a fatal flaw.

SpaceX’s shape works for SpaceX because of Elon, access to capital, first mover momentum, and many other SpaceX-specific factors. Trying to emulate SpaceX’s exact shape without the same foundation doesn’t work, as many have discovered.

Instead, it’s helpful to consider the current market dynamics, the resources the company can bring to bear, and the program’s end goal — to maximize market share, achieve profitability quickly, limit technical risk, or something else entirely.

Many shapes can succeed. Ultimately, what these case studies show is that intentionality matters the most.